In November, a new finance climate goal for 2035 was set. Less than two months later, the goal has already failed. The 29th COP, the annual conference organized by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, ended on November 24, 2024. COP 29 was the second largest COP in history, second only to COP 28. Some referred to the conference as the “Finance COP,” with the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) on climate finance being a key takeaway. As stated in the advanced unedited version of the document, the goal focuses on keeping the “increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels” by increasing funding.

This 1.5°C goal is significant. Experts say an increase higher than 1.5°C would make the climate crisis significantly more dangerous and notably harder to reverse. According to a New York Times report, if the global temperature increased by 1.5°C, about 14% of the world’s population would experience severe heat waves at least once every five years.

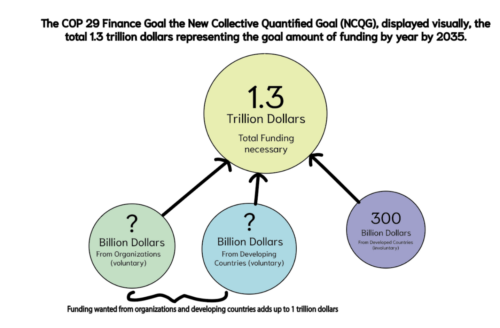

The NCQG aims to raise 1.3 trillion dollars annually for climate efforts by 2035, which is estimated to be the amount needed to keep global temperatures from rising more than 1.5°C. The goal requires developed countries to contribute 300 billion dollars annually. Private companies, lenders, and developing countries are asked to make voluntary donations to cover the 1 trillion dollar gap between 1.3 trillion and 300 billion.

Some have criticized the deal because it enables rich countries to contribute less and forces developing countries and organizations to make up the rest. The New York Times quoted the Indian representative at the conference, Chandni Raina, who called the amount a “paltry sum” and stated, “I am sorry to say that we cannot accept it. We seek a much higher ambition from developed countries.” Bolivian, Nigerian, and Fijian representatives also criticized the deal harshly.

These points are entirely valid. A New York Times analysis done in 2021 determined that, historically, developed countries are responsible for 50% of emissions despite developed countries containing only 12% of the world’s population. Developed countries should be responsible for gathering the majority of the funding for climate efforts, as they are the leading cause of the crisis. Developing countries and organizations should not be accountable for contributing more than three times more funding than developed countries, a critical flaw in the financial goal.

Still, the finance plan has the potential to be somewhat of a success, on the contingency that countries and organizations alike step up. The conference did not set required amounts for how much individual developed countries should contribute to the 300 billion dollar goal. Besides the desire to save the planet from the climate crisis and to have a good international reputation, there is no incentive to contribute a lot. There is even less enforcement for developing countries and organizations, as they have no obligation to provide anything.

However, even if countries and organizations follow through on the plan, technically, it will still fail. Last week, the 2024 global average global temperature was announced, and the increase has reached 1.6 °C. Although this is devastating, it is not a reason to give up. Every tenth of a degree matters and efforts should continue to prevent the global temperature from rising any more than it already has.

Shifts in the United States Government will undoubtedly continue to impact these efforts. Donald Trump’s upcoming entry into public office influenced the conference’s outcomes and will significantly affect the future of climate policy. Carbon Brief states that “Michai Robertson, lead finance negotiator for AOSIS, told Politico that Trump’s victory “changed” what the US “could have provided” – as the outgoing Biden team was in no position to commit to an uptick in spending.” The financial deal would have been more substantial if the United States had been able to commit to a more ambitious goal.

Upon his return to public office, Trump plans to take the US out of the Paris Agreement and thus is not expected to abide by the deals made at COP 29, which affects whether or not the 300 billion dollar goal will be met. Trump’s government also plans to take funding from Ukraine, which European countries may decide to compensate for. Thus, less money is available for transitions to clean energy and other climate efforts. Yet, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), the United States’s “Governors, mayors, and CEOs reassured conferencegoers that if Trump exits the global climate conversation, subnational actors and private companies will ensure the U.S. stays engaged.”

Surprisingly, another nation is stepping up as the US is fading away from climate policy. China has recently surpassed the EU for the most emissions; however, the country had almost 1,000 delegates at the conference, and the behavior of these representatives was described as “unusually cooperative” by CSIS. The center reported that Chinese delegates mediated between parties to produce the final financial plan. China also pledged to reach carbon neutrality by 2060 and announced that they have spent 24.5 billion US dollars thus far on climate efforts for developing countries.

Some plans for the conference did not end up coming to fruition. The results of the COP 28 Global Stocktake (GST), a process created in the Paris Agreement that functions to assess whether or not countries individually are meeting financial goals, were supposed to be followed up on but were not. In addition, negotiations on Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCS) and countries’ individual plans to limit emissions were postponed and set to be the topic for COP 30 in Belem, Brazil, in November of 2025.

Going forward in climate policy, urgency is essential. Although the finance deal is far too lenient with developed countries and important topics were postponed, COP 29 created meaningful plans and agreements. However, without follow-through, the deals mean nothing. Organizations, developing countries, and especially developed countries must step up for the conference to have an impact. The United States and China, as still the two biggest emitters, must continue cutting greenhouse gasses down, even if Trump’s presidency limits the United State’s role in international climate change policy.

Although the cost of 1.3 trillion dollars is high, the cost of repairs is far higher. A journal article published by Nature states that the projected cost of damages from climate change is estimated to be 38 trillion dollars if goals are not met, even if the global temperature never rises more than 2 °C.

A recent reminder of the importance of climate policy burst into the public eye last week. The raging fires in LA have already been associated with climate change, specifically with hydroclimate whiplash, which occurs when rain levels fluctuate from very high to very low in short periods of time. The fires are devastating, and a prime example of the destructive disasters that could continue to occur more frequently. The catastrophe should serve as a wake-up call and spur to action to ensure that the COP 29 goals will become reality before it is too late.