In the wake of the Dark and Middle Ages, as Europe staggered from the devastating aftermaths of the plague, the continent was ready for something extraordinary: enlightenment. The French word Renaissance translates to “rebirth,” and that is precisely what occurred from the 14th to 16th centuries – a dramatic explosion of culture, art, science, and intellectual exploration across Europe which is credited by some as the birth of the modern world. This was no ordinary revival indeed.

Gone were the rigid structures of medieval values, replaced by a newfound appreciation of individual worth and intellectual freedom. Classical learning was reborn and humanism, a philosophy which placed the dignity and worth of individuals at the center of scholarly and artistic pursuits, emerged. Most notably, this period gave rise to extraordinary achievements and works that remain examples of human potential and creativity and are revered to this day.

The Catholic Church played an instrumental role in supporting this flourishing of the arts, which became some of the most celebrated legacies of the Renaissance. As a major benefactor, the Church financed many of the era’s great works, while Rome and the Vatican evolved into an epicenter of cultural advancement and attracted artists and thinkers from across Europe. Under the Church’s guidance, art became a powerful medium that explored the divine, the human, and the intersection between the two. Mr. Scott Wolfson, the chair of Fieldston Upper’s Art Department, remarks, “The Renaissance demonstrated an interest in connecting people to the divine on a physical and emotional level. As a result, the figures and space of the artworks were more naturalistic and full of emotional complexity. This is seen through figures’ actions and expressions, and the spaces were more believable and thus, more inhabitable. People could see a scene from the Bible and connect to the stories on a tangible and personal level.”

Cue the entrance of legendary artists like Da Vinci, Raphael, and Michelangelo, who rose to prominence and created works like the Last Supper, Transfiguration, Pieta and David respectively. But soon, the latter would create another masterpiece to rise above (both figuratively and literally) them all – something that would not only become one of the defining achievements of the Renaissance but one of the greatest artistic accomplishments in history: the frescoes that adorn the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Commissioned by Pope Julius II in 1508, the project took Michelangelo four years to complete, though he returned to work on the chapel until his death. On November 1, 1512, the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling was unveiled to the public.

Standing beneath Michelangelo’s timeless depictions, one is inevitably reminded of the power of art. As Fieldston News faculty advisor Mr. Montera so aptly puts it, “Funny thing happens when you look up.”

This Month in History

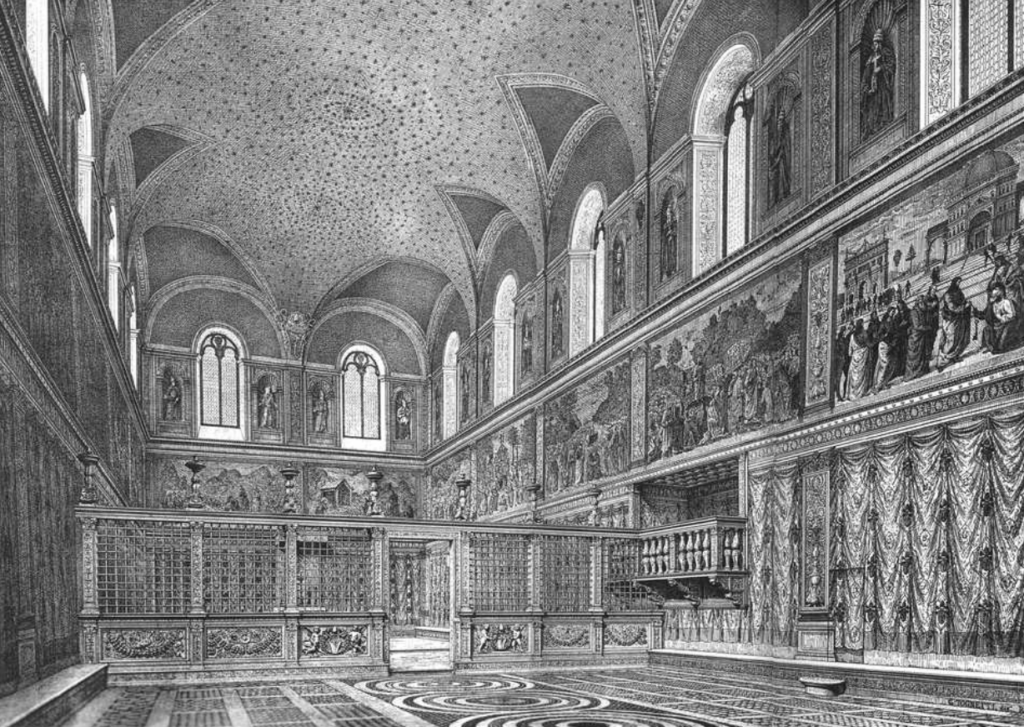

In 1504, a giant crack developed in the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. The building was relatively new, having been commissioned by Pope Sixtus IV around 1473 and completed around 1481. The interior had already been decorated by some of the most esteemed artists of the time, including Sandro Botticelli, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Cosimo Rosselli, and Pietro Perugino. The renovation of the ceiling presented an opportunity to further expand the art that adorned the chapel walls, yet it demanded an artist of extraordinary skill. Pope Julius II, who was known for his very ambitious and grand artistic and architectural undertakings (he wished his tomb to be adorned with 40 statues), sought to commission a work that would reflect the glory and authority of the Church. The task was eventually entrusted to a man who was increasingly establishing himself within the artistic world, whose unparalleled talent would eventually earn him the title of “Il Divino” (The Divine One), and work that would influence generations of artists and leave an indelible mark on Western art history. Mr Wolfson notes, “By commissioning Michelangelo, one of the most revered artists in Western Europe at this time, to decorate over 5000 square feet of space in the Sistine Chapel, the Pope and therefore the Catholic Church were promoting a sense of power and awe.”

What the Chapel May Have Looked Like Prior to Michelangelo’s Frescoes

(Source: Smart History)

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni was born on March 6, 1475 in the Republic of Florence. His early artistic career began under the tutelage of Domencio Ghirlandaio, one of the city’s most esteemed painters. Soon after, he shifted his focus to sculpture under the patronage of Lorenzo de’Medici “the Magnificent.” The Medici family, as those who have taken Modern World History class may recall, were a Florentine banking family and prominent patrons of the arts, education, and culture in Florence. Florence was regarded at the time as the leading center of art, and it produced some of the best painters and sculptors in Europe. However, as Florence’s ability to offer significant commissions waned, many of its most talented artists, including da Vinci, sought opportunities elsewhere. By 1494, shortly before the Medicis were ousted from power, Michelangelo followed the exodus (no pun intended), finding opportunities in Rome. It was there he sculpted the Pieta in 1498. He then returned to Florence in 1501, where he carved David from a discarded block of marble, turning it into a masterpiece that would become a symbol of the Florentine Republic. In 1505, Michelangelo was summoned back to Rome by Pope Juilius II to work on his aforementioned tomb. However, this project was repeatedly interrupted as Julius assigned other works for the artist, one of these being the Sistine Chapel Ceiling.

Michelangelo was initially reluctant to accept the commission. Known primarily as a sculptor, he considered himself inexperienced in fresco painting and hesitated to take on such a vast endeavor. Under the pope’s insistence, Michelangelo agreed to the task and began work on the ceiling in 1508. While some historians suggest that the popular image of him lying on his back with paint and plaster dripping into his eyes is likely a myth, there is no doubt that he worked tirelessly over the next four years.

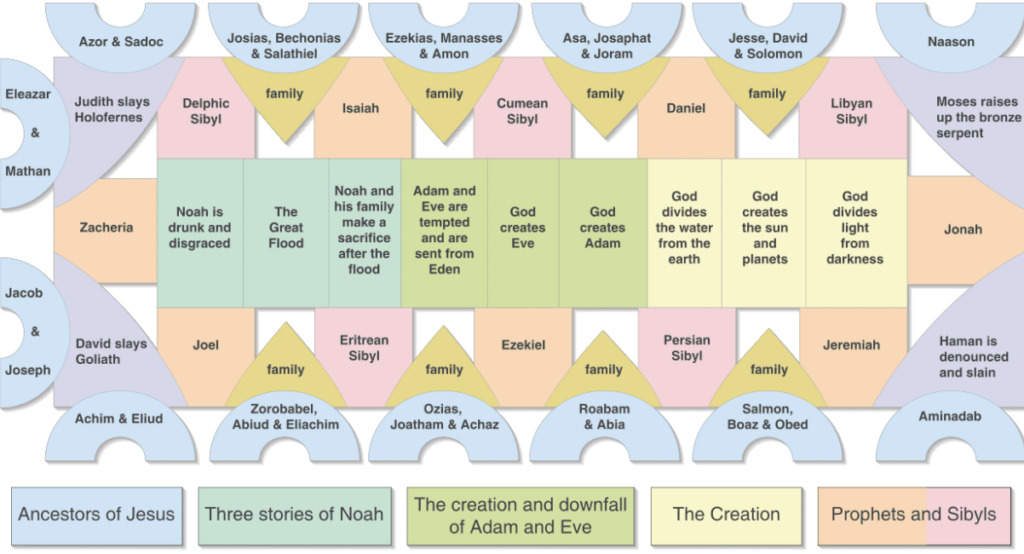

The original plan for the ceiling, proposed by the pope, was a geometric design surrounded by the Twelve Apostles, but Michelangelo suggested the famous scenes from the Old Testament instead. The ceiling was transformed into a sweeping visual narrative of the Book of Genesis, divided into three sections: The Creation of the Heavens and Earth; The Creation of Adam and Eve and the Expulsion from the Garden of Eden and finally Noah and the Great Flood. Ignundi, prophets, and sibyls (ancient seers who foretold the coming of Christ) are placed along the perimeter. In the corner are scenes depicting the Salvation of Israel.

Layout of the Sistine Chapel Ceiling (Source: Smart History)

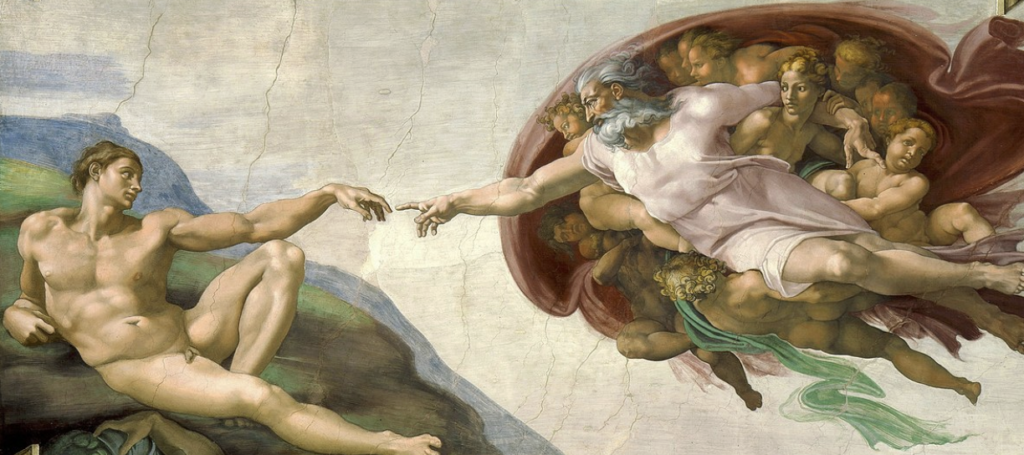

Mr. Wolfson states, “Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling doesn’t simply tell the story of the Creation of the Earth or the Creation of Adam or the story of Noah, but represents ideas about the relationship between the earthly and the divine.” And nowhere is this more evident than The Creation of Adam, one of the most celebrated panels in art history. Here, Michelangelo portrays God as powerful, yet distinctly human-like. This isn’t some distant, untouchable abstract deity; Michelangelo’s depiction is familiar and somehow approachable while still commanding reverence. This scene shows the gift of life from God to humanity, and Adam is clearly dependent on the divine touch of his Creator, or God, for his very existence: he is reaching up to him, their fingers nearly touching.

The Creation of Adam (Source: Wikipedia)

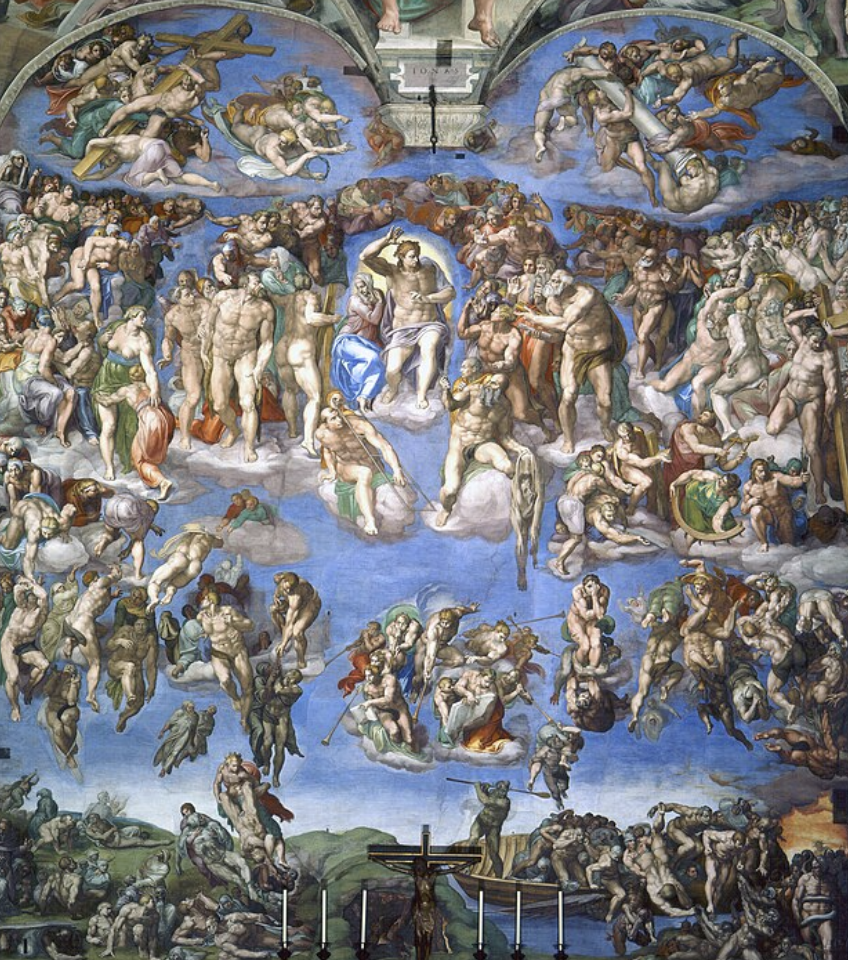

Michelangelo’s ceiling features over 300 figures, each painted with astonishing anatomical precision. Although his work on the ceiling itself concluded in 1512, he returned to the Chapel to paint The Last Judgment on the wall above the altar for Pope Paul III in 1534. Mr. Wolfson again notes, “Jesus was a human being made of flesh and blood and he inhabited spaces that we, too, could imagine inhabiting.” Once again, Michelangelo bridges the gap between the divine and the early. His paintings make the sacred feel familiar and relatable, yet they retain an overwhelming sense of awe and reverence and remind viewers of humanity’s dependence on God’s sustaining power.

The Last Judgment (Source: Wikipedia)

Today, the Sistine Chapel remains one of the most iconic and revered landmarks in the world, attracting millions of visitors each year. And of course, Michelangelo’s ceiling, with its innumerable figures in complex, twisting poses and its exuberant use of color, the chief source of the Mannerist style, a movement that emerged after the High Renaissance, continues to be one of the most celebrated works of human creativity and inspires awe across the globe.

Perhaps, Michelangelo said it best: “The true work of art is but a shadow of the divine perfection.”

Source: World History Encyclopedia