The week of September 15th has been quite significant in American history. Some key events include the Mayflower’s departure from England, the Battle of Antietam beginning and ending after twelve hours, Chester Arthur (who is that?!) becoming the third president to serve within one year, George Washington laying the cornerstone for the Capitol building, and Washington publishing his farewell address as president.

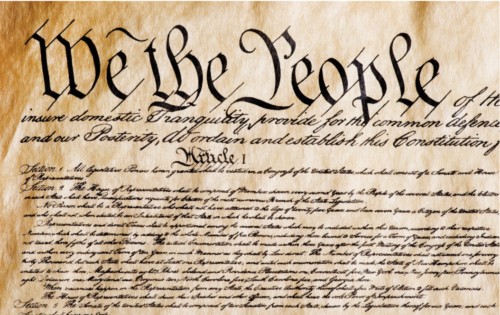

Perhaps the most important moment that occurred this week was the signing of the U.S. Constitution on September 17, 1787, a sad day for John Hancock, whose iconic signature may have graced the Declaration of Independence, but was not seen on this new charter of governance. Other important names missing were Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, who were on diplomatic missions during the time of signing. Instead, thirty-nine signatures covered the parchment of the cornerstone (partially laid by George Washington, I suppose) of the American government.

This is A Recent Week In History.

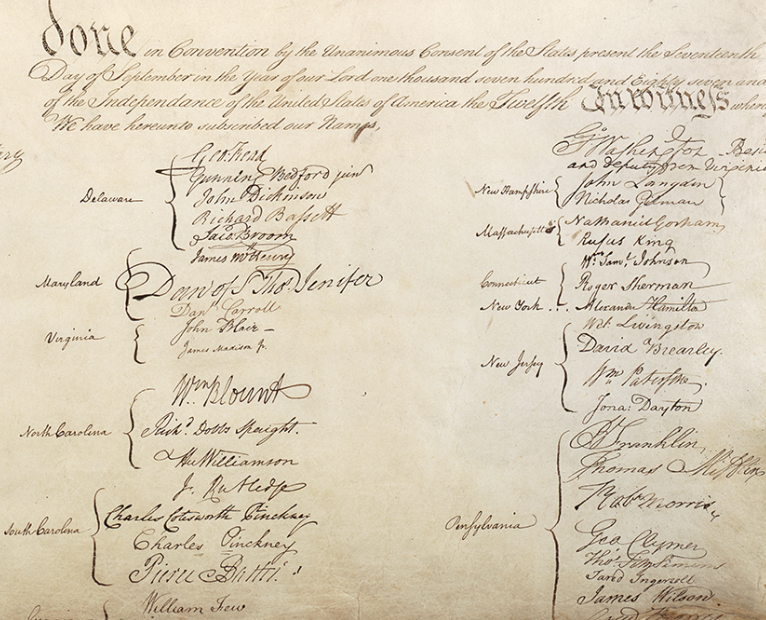

Signatures on the Constitution (Source: The National Archives)

“…that these dead shall not have died in vain– that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth, ” declared President Abraham Lincoln after Gettysburg, the bloodiest battle in the bloodiest war in American history to this day. How could America continue as a united nation after such devastation? The answer lay in Lincoln’s adamant assertion that the government – the very thing that unites this nation – is formed by, of, and for its citizens, who will and must not let it falter.

The Constitution’s opening phrase “We the People” is not just rhetoric; it is a declaration of who holds the power in our country – an evolution of the ideals of self governance put forth by the Declaration of Independence. The American government exists not as an entity ruling over citizens, but as a creation of the people, designed to serve them and ensure their rights. Known as one of, if not the most brilliant document in political history, the United States Constitution is unique in that it is a living document, capable of being amended, and delegates authority in a way that ensures power ultimately rests with the people.

Designing the Constitution was no easy feat. After the Declaration of Independence and in the midst of the Revolutionary War, it became clear that a national government was necessary to prevent states from conducting their own foreign diplomacy. The Articles of Confederation served as the first national framework for the United States from 1781 to 1789. It was ratified by the Continental Congress, a convention of delegates from each of the thirteen colonies that became the governing body during the American Revolution. The Articles may have created a loose union of states on paper, but in practice the federal government had little authority to enforce its requests. The delegates had intended this because they didn’t want to be under a tyrannical government again, but issues involving particularly money and troops resulted in Congress’ inability to effectively govern the young nation.

Shays’ Rebellion was one of the major catalysts for the creation of the United States Constitution because it exposed the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation. The American Revolution hadn’t fulfilled its promise to the many who had risked their lives serving in their state militias and the Continental Army. They received little pay for their military service, and their farms and possessions were seized by debt collectors to support the country, which was in a severe economic recession. Although the United States did not have a standard currency and had a shortage of cash at the time, state courts only took paper money to repay obligations, so many men who had fought for their freedom were now behind bars in debtors’ prisons. Discontent smoldered from New Hampshire to South Carolina, and eventually, Daniel Shays led a violent uprising against debt collection in Massachusetts with fellow disgruntled former soldiers. In August 1786, Shays and over 500 veterans marched to the county court in Northampton, successfully shutting it down to prevent further property seizures and debt collections. In January of 1787, Shays and 1,500 men stormed a federal armory in Springfield. The rebellion was quelled in February 1787, and incentivized Revolutionary War general and hero George Washington’s return to public life. He became a strong advocate of creating a federal government that would address the pressing economic and political needs of the new nation.

On May 25, 1787, delegates representing every state except Rhode Island convened at the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia. Washington, the then-delegate from Virginia, was elected as the convention president. The delegates shuttered the windows of the statehouse and swore secrecy so that they could speak freely. They abandoned revising the Articles of Confederation and instead devised a federal organization limited by a system of checks and balances over three branches of government: the federal, judicial, and executive. The most intense debates were over state representation in Congress, ultimately leading to the Connecticut Compromise. A bicameral legislature with proportional representation in the lower House of Representatives and equal representation in the higher house, the Senate, was decided on. After a summer of fierce debate and many preliminary write ups, a draft of the Constitution was completed.

The states approved the draft of the Constitution on Saturday, September 15, 1787. Jacob Shallus, the assistant clerk of the Pennsylvania State Assembly, hand wrote the 4,543 words in the final copy of the Constitution for a 30 dollar salary. On September 17, the following Monday, the document was ready for signing. George Washington penned his name first, followed by each delegate descending from north to south. 39 of the 42 men present signed the Constitution; George Mason, Elbridge Gerry, and Edmund Randoplh did not sign due to the lack of a bill of rights.

Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States (Howard Chandler Christy, 1940; Source: Capitol Architect)

9 of the 13 states needed to ratify the document in order to enact the new government, as dictated by Article VII of the Constitution. Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, and Connecticut were quick to ratify it that December, but other states, namely Massachusetts, were hesitant and even opposed the document, concerned about the lack of explicit protections for individual rights. In February, a compromise was reached that allowed for ratification with the promise of future amendments. Massachusetts, Maryland, and South Carolina narrowly ratified the Constitution. It was then ratified by New Hampshire on June 21, 1788, making it binding, with Virginia and New York following suit in June and July. The first Congress adopted the Bill of Rights in 1789, consisting of 12 amendments, 10 of which were ratified by 1791. Rhode Island, initially resistant, ratified the Constitution on May 29, 1790, becoming the last of the original 13 colonies to join the United States.

Nowadays, the Constitution faces significant criticism, particularly regarding its relevance and effectiveness in addressing current societal issues (something Mx. Amore’s Current Events classes discussed a couple of weeks ago). Amending the Constitution has become increasingly challenging, with the last amendment ratified in the 1980s concerning the salaries of Senators—an issue that holds little relevance for the average American. Concerns also persist about the growing power of the Supreme Court and undemocratic practices like the Electoral College, filibustering, and gerrymandering.

Alan Jenkins, a Professor of Practice at Harvard Law School, notes that the “[The Constitution] brilliantly articulated the idea of fundamental equality — human equality. It beautifully articulated the notion that government’s power flows from the people, and that government serves the people. But it was fundamentally flawed in preserving and propping up slavery, that ultimate form of inequality. And for excluding women, non-white people, indigenous people, non-property owners, from the definition of ‘the people.’” He also says, however, that “our Constitution gives us most of what we need to enjoy equal justice and opportunity and the full range of human rights. But we see not only Supreme Court justices, but many courts around the country, that are either hesitant or actively opposed to making it so.”

As new generations grapple with contemporary issues, the document’s original language and intentions are put to the test. The flexibility inherent in constitutional interpretation allows for progress, but it can also lead to divisive outcomes that disenfranchise many. For the Constitution to remain relevant, it must reflect the changing landscape of America.

The Constitution of the United States stands as the oldest written constitution in operation in the world, but how much longer can it endure? Civilizations strive for permanence, but they are built on the impermanent: the ambitions, emotions, and values of individuals. Laws are created to safeguard justice, but they can be interpreted in harmful ways if they are too broad, and can be deemed authoritarian if they are too strict.

Perhaps the true aim of a civilization is not to be immortal, but to continually pursue balance, to adapt, and to remain vigilant against forces that threaten to destroy it. The ability to evolve, to rise above corruption and stagnation, to find strength in unity is how, as Mr. Lincoln puts it, “the government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from this earth.”

American Progress by John Gast, 1872 (Source: Library of Congress)