Winston Churchill, who you may know from the excellent biographies he wrote about his father, himself, or his ancestor, John Churchill, the first Duke of Marlborough, channeled the words of George Santayana, by saying, “Those that fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.”

By learning about the past, those living in the present can come to understand how we got here, where we came from, and most importantly, what to do next. The Fall of Rome can teach us about the consequences of decentralized power and overexpansion. The Treaty of Versailles following the Great War warns us about punitive peace settlements and their role in fostering resentment, leading to the eventual rise of authoritarianism and World War II. The Industrial Revolution demonstrates the potential of technological advancement, but the dilemmas of labor exploitation and child labor. Revolutions — French, American, you name it — remind us of the dangers of social inequality and unchecked autocratic rule, but also of the power we have as individuals to fight oppressive or unfair governments. Embedded in history are lessons, hundreds of thousands of them, as well as trivia to impress your friends and family with: for instance, Churchill wrote 43 books including the aforementioned biographies as well as a richly illustrated essay collection on contemporary statesmen (Hindenburg, Hitler, Roosevelt), and won a Nobel Prize in Literature.

Either way, the rich history of humanity becomes more and more apparent as one researches the events that unfolded this exact week. This column will discuss these events, serving not only as a fun source of information but also to bring awareness of our past.

Last Week In History

On September 8th, 1664, the English seized control of the Dutch-controlled city of New Amsterdam. The colony was renamed New York in honor of James, the Duke of York, who would later assume the throne as King James II of England. The territory had been given to James by his brother, the reigning Charles II, through a charter. Both the location and the rapidly developing port of commerce and trade made New York highly valuable to the growing British empire. Today, New York still stands, its prominence on the global stage having only grown since centuries prior.

European nations swept the globe in the 16th and 17th centuries – The Age of Exploration — and the newly formed United Provinces of the Netherlands were no exception. The seven provinces that made up the federal republic had recently seceded from Spanish rule in 1579, and were eager to join the aspiring Western empires in colonizing the entire continent that had just been discovered – The New World.

In 1609, the Dutch sponsored Henry Hudson to embark on a westward journey. Hudson sought to pursue the Northwest Passage, a fabled sea route that would supposedly connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Instead, he found a magnificent harbor and a vast river that would later bear his name. Hudson claimed the land for the Dutch, and soon, similar settlements would appear along the Delaware and Connecticut Rivers.

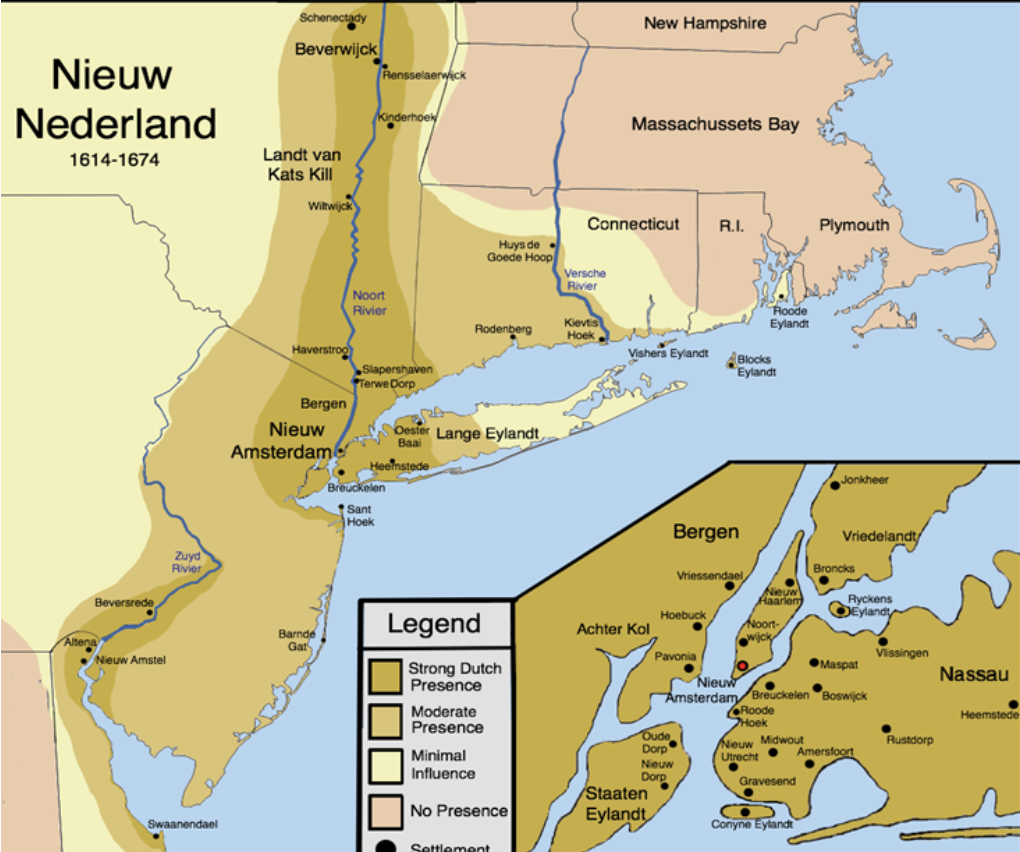

New Amsterdam extended from the Delmarva Peninsula to southwestern Cape Cod. It was founded primarily as a commercial enterprise, with its main purpose being to capitalize on the fur trade. Colonists from all over Europe were lured by the promise of valuable trade, fertile farmland, and vast forests. Beaver pelts in particular were coveted to manufacture fashionable European garments. Merchants and investors primarily ran business arrangements in New Netherland until the creation of Dutch West India Company in 1621, the counterpart to the already existing Dutch East India Company. Unlike many European colonies, which had religious or military motivations, New Netherland was driven by business interests, serving as a strategic trading post for goods flowing between Europe and the Americas.

Source: National Park Service

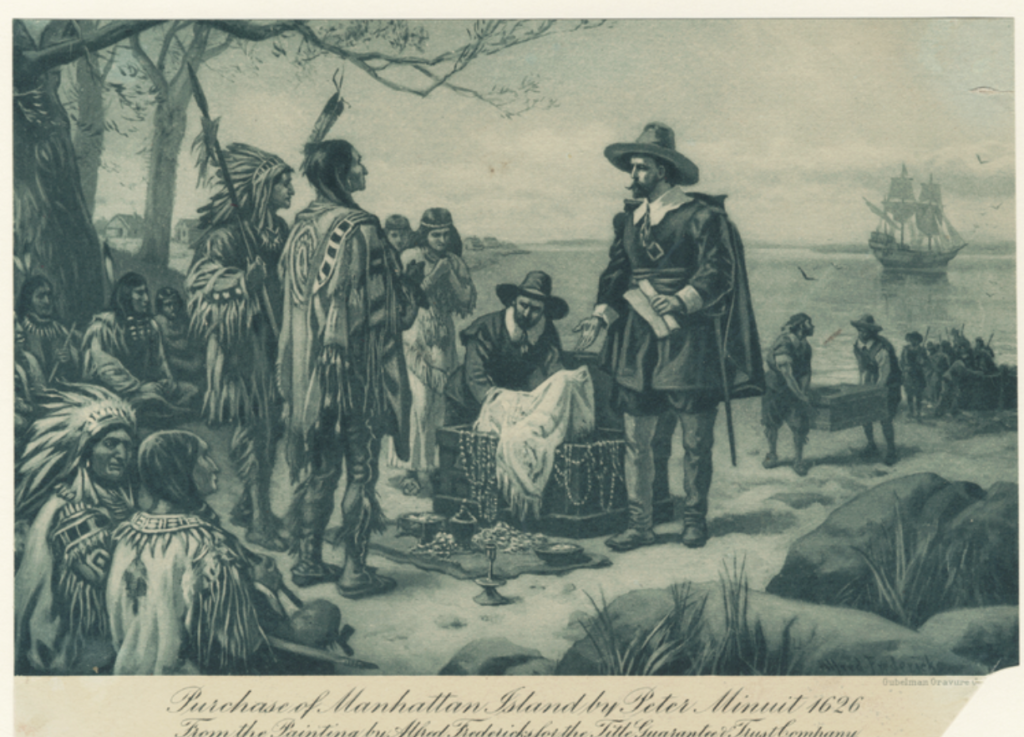

In 1626, Peter Minuit, the director-governor of New Netherland, famously purchased the island of Manhattan from the Lenape tribe for the modern-day equivalent of 24 dollars. It was christened “New Amsterdam”, and with a natural harbor that accommodated a wide variety of ships and provided direct access to the Atlantic Ocean, the settlement quickly became the locus of New Netherland commerce.

The city was cosmopolitan for its time. The Dutch were extremely tolerant, and while the Dutch Reformed Church was the official faith, the colony allowed the practice of other religions, a rarity for other New World Colonies (Case in point: Read Nathaniel Hawthrone’s Scarlet Letter). Women were also allowed to participate in politics and trade. This diversity and tolerance was one of the key factors contributing to the colony’s prosperity. By the 1650s, New Amsterdam had solidified its place as the bustling capital of New Netherlands.

The Purchase of Manhattan Island by Alfred Fredricks. Source: New York Public Library

The British Empire, who were relatively late to the colonial race, quickly set their sights on New Amsterdam. The British knew that the acquisition of such a valuable place – culturally and economically, would cement their position in the Americas.

The handover of New Amsterdam was emblematic of the larger shifts in power occurring in the world at the time. England’s consolidation of territories in North America was a precursor to the rise of the British Empire, which would dominate global politics and trade for centuries. New Amsterdam was facing some internal struggles, and the First Anglo-Dutch had occurred around a decade earlier. The unpopular and final director-governor of New Amsterdam, Peter Stuyvesant (would he have been more popular if his name was Fieldston?) had no choice but to hand over the region to an English naval squadron that entered the bay in 1664.

New York was just as profitable as the British hoped, continuing to grow under English rule. In 1686, it became the first city to receive a royal charter, and after the American Revolution, it became the first capital of the United States.

The legacy of New Amsterdam lives on in modern-day New York, from the city’s street names to its celebration of cultural diversity —qualities that were already taking root under Dutch rule. Coney Island comes from the Dutch word for rabbit, “konijn”, since the area had a large population of wild rabbits, and the Bowery comes from the Dutch word for “farm”, presumably a nod to New Amsterdam’s agricultural significance. The haphazard streets of Lower Manhattan are remnants of the original streets, modeled after those of European towns.

The name change marked not only a transition in governance but the birth of one of the most influential cities on Earth – a global metropolis we know, love, and live in today. It is, after all, known as the greatest city in the world.

For those wanting to read more about New Amsterdam’s early days, consider reading “Island at the Center of the World,” by Russell Shorto.