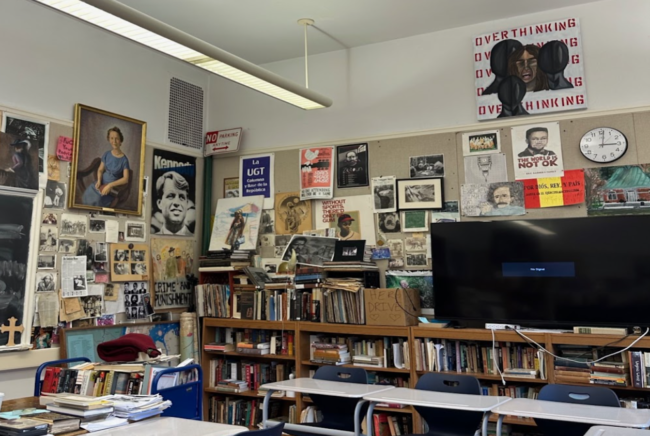

Adorned in homages to histories global, local and personal alike, history teacher Bob Montera’s classroom is an extension of the intellectualism fostered within it. Objects ranging from a set of student-gifted world history action figures representative of the numerous classes Montera has taught to a Zulu “assegai” previously used in 19th century combat cement the space as an oasis for the ideal curious history student. In fact, the maximalist nature of room 112 makes it not only a classroom but an experience.

Montera obtained the room by default. Nobody else wanted it. “The senior corridor had a reputation for being noisy and wild,” and Montera gladly occupied 112 because of its spacious build, high ceilings and view of the tree-lined Manhattan College Parkway. Soon after, he caught onto the fact that the rumors about Fieldston seniors “were simply not true. Seniors are and have always been delightful.”

Initially, 112 was a science lab below the original Fieldston School Library (1928-1969). The space was a bleak, unadorned classroom cleared out at each school year’s end. So, Montera brought in a few books. “Ronald Reagan was president. George Herbert Walker Bush was about to be elected. I was teaching Advanced Placement American History, US since 1940, Journalism and 8th-grade Ancient and Medieval World History. That started the collection.”

In time, the room became a home to ideas, student work, historical archives, Fieldston relics, books and encyclopedias, memorabilia, repurposed treasures and supplementary texts for Montera’s other classes: African Studies, Science and History, History of the Working Class, Native American Studies, Film and Literature, Russian Literature, Modern European Literature, and Interdisciplinary Senior Seminar.

Late last spring, I perused the space filled with thousands of books and the omnipresent tune of WQXR 105.9, the classical radio station.

THE LIBRARY

To try and make sense of room 112’s beautifully chaotic atmosphere, it is crucial to recognize the space’s very basis: books. There are probably 3,500 books in the room. Beneath collages of photographs, paintings and political posters lies a library of varied volumes. As Montera accumulated more and more works and continuously reorganized his classroom, books found themselves stored anywhere and everywhere though predominantly in shelves pressed against the left and right walls.

Regarding his class library, Montera noted, “I probably started with a handful of books and there were some old, white bookshelves in this room- this room used to be a science classroom- and I started to bring in books that I needed for my classes. […] The expectation was that at the end of each school year you would remove any and all books and the place would be thoroughly cleaned and then you would come back the next year, which was never fully guaranteed, and then you could set up again. Three or four years of doing this, acquiring more and more books and teaching more classes, I decided ‘I’m just leaving it there and let’s see if anyone complains about me.’ No one complained, and that was like an open door…the books just gathered.” That was the beginning of a library and archive.

Room 112’s library is arranged with a nod towards historical and subject categorization. On the western end of the classroom, world history and world literature lines wooden shelves as specialized history like that of warfare and epidemics sits perched atop said shelves interspersed with an ensemble of vinyl records and a collection of art history texts. To the east, American history, art and culture is mixed in with a treasured hand-me-down set of the Encyclopedia of Philosophy and Encyclopedia Judaica. Carts positioned on either side of Montera’s desk signify expansion into Asian studies, architecture, African studies and various other areas of interest.

Montera believes the divide in topic between his shelves and sides of the classroom represents the various roles he has taken on as a teacher of literature, film and numerous histories. Fundamentally, his books serve a purpose far greater than complimenting the room with yet another hint of academia; they emphasize Montera’s storied tenure as an educator and provide tales of various civilizations, figures, worlds and histories.

Montera commented, “[The library] is not quite a Dewey-decimal system, but you can locate things and when students need books that have been taken out of the Tate Library, they can usually find a copy here and borrow them so long as they fill out a little index card saying, ‘I’ve got your book’ and the books always come home.”

While Montera’s shelves are a true trove of yearbooks, records, novels, student projects and encyclopedias alike, they only begin to let onto the rest of the room’s story.

THE WALLS

Perhaps the most poignant feature of Montera’s room is not one sole entity but rather four walls plastered with the musings of minds both student and historical. The walls encapsulate most everything that has existed within them.

Montera explained, “I can look at the wall and I can sort of see the classes over the years; I can see my advisories over the years; I can see my students; I can see their assignments, photographs that they made for my class, or paintings they made for one of my classes or maybe for some other teacher that I took a liking to. Sometimes, students would just say, ‘I’m hanging this up.’”

In doing so, students past and present contribute to the classroom’s legacy as an ever-evolving gallery.

Spanish Civil War posters, Central Park sketches, magnets of nearly all 46 presidents, posters of Woodstock, Great Gatsby projects and a portrait of former head of school Victoria Wagner (saved from a future spent in storage) all reside harmoniously on room 112’s walls. One might ask: To what purpose?

“When students are in this room, I think what they like about it is that there’s always something new to find. Whether it’s that time before class starts, or on your way out or even in those moments when you’re just spacing out a little bit- to look up and to see a painting… I think it helps you relax and sometimes just allows you to collect your thoughts; I think sometimes it takes you off into some imaginative, magical place.”

This theory regarding the importance of the classroom always having something new to discover led me to inquire about the ways in which Montera strives to model his teaching after the interdisciplinary nature of his physical classroom environment. Focusing in on the word “interdisciplinary,” Montera explained his classroom and teaching tend to fall under the word’s definition meaning he and room 112 either “do not have the attention to focus in on one particular subject or [are] drawn to multiple connections.” Sticking with the latter, Montera stated that any class should allow itself to travel between disciplines and worlds. His room does so by becoming “a forum for students and their ideas, a workshop, the place where the Fieldston News meets regularly, a performance space” and so much more.

Ending his classroom’s tour on a note of advice Montera shared, “Objects speak to you. It could be a color, it could be a texture, it could be anything.” Whether you are a seasoned treasure hunter like Montera or merely an observer of your surroundings, I suggest you take a deeper look at the objects, individuals and environments around you; they just might have some wondrous stories to share.