Most students know Karen Drohan, an affable upper school history teacher entering her 9th year in the Fieldston community. What they may not know is that her late husband, Mike Martineau, was a successful television writer in the 1990s and early 2000s. Or, that Drohan spent this summer taking shifts on the picket line for the Writers Guild of America.

The WGA strike will enter its 18th week this September, after four months of dispute with the AMPTP (Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers). Along with demands for higher pay and better residuals, the protests are partially predicated on anxieties about recent technological developments. The last WGA strike occurred in 2007/2008 amid concerns about the emergence of streaming services. Now, writers face the encroaching threat of artificial intelligence, which could potentially be used to create new scripts and endanger jobs. Furthermore, AI lacks any form of identity, often the key to a compelling story. “We’re not going to know what it means for another decade,” says Drohan. “But the Writers Guild has to get ahead of that and set some boundaries so that writers will have protections around AI.”

Another point of contention is microrooms. Previously, the television industry would assign seven or eight writers to collaborate for the duration of a show’s season. Over 8-9 months, they’d meet in a writer’s room to brainstorm, script, and compose on the fly if jokes didn’t land as intended. Microrooms, on the other hand, consist of five or six writers. They’ll spend a few weeks plotting out the whole season, and once everything is written, they’re done. Rather than getting paid for every single week that they’d usually be in the writer’s room, they’d only get paid for the short period that they were there. This would additionally diminish the number of automatic deposits into their pension funds, which occur with each paycheck.

For Drohan, her husband’s WGA membership was incredibly valuable over the years. Although he passed away in 2012, she continues to receive his residual checks, and his health insurance covered the family from 1992 to his death in 2012. “I had two children with the health insurance, I had surgery, my husband had surgery and both of my children ended up getting surgeries. It’s the kind of health insurance every American should have.” Today, writers are at risk of losing these benefits. To qualify for health insurance, they must earn a minimum salary, either through ongoing work or residual checks. However, if both opportunities are being cut, many aren’t able to make the Guild’s minimum. Without a partner who works outside of the entertainment industry, it’s difficult to survive.

In response, many of Drohan’s close friends are taking to the picket lines. “Lots, lots and lots of people that I love very much are profoundly affected by this,” says Drohan. “I have a friend who’s a television writer who just took a job as a tutor at a community college. I know people who said, ‘Okay, I can make it six months. But I don’t know what I’m going to do after six months.’ I have a friend who has a child with special needs, who is terrified of losing insurance – then, what does she do? She’s a single parent, with a child with special needs and she doesn’t have a partner. What happens?”

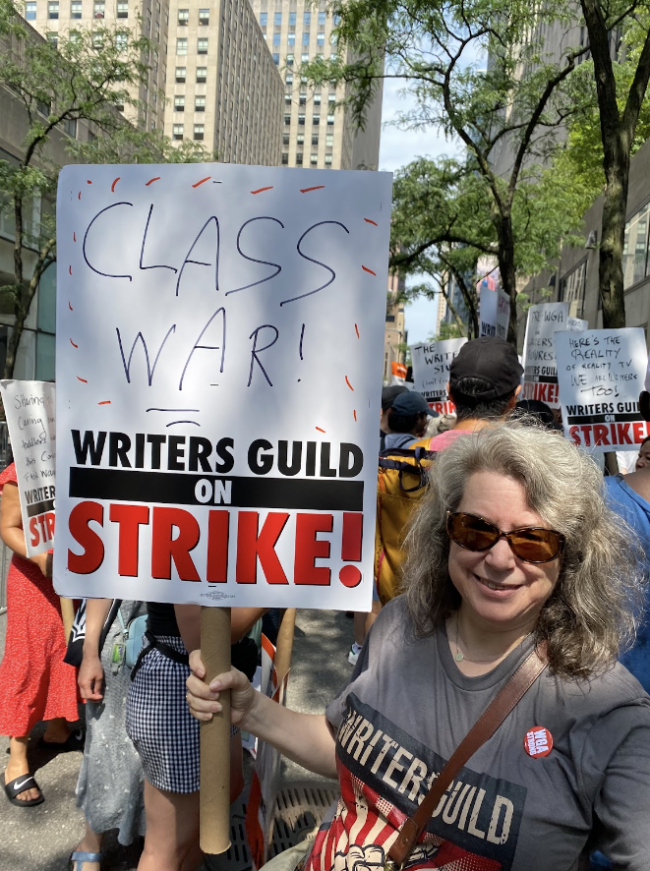

Drohan herself understands that for a strike to be effective, the picket lines require constant participation. Therefore, she and her children have volunteered as additional bodies at several WGA gatherings, which are usually themed. For example, Drohan’s husband worked mostly in comedies, and Comedy Writer Support Day happened to fall on his birthday, July 26. On August 22, the AFL-CIO (American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations) called a National Day of Solidarity. Drohan and her children joined a brimming city block at Hudson Yards, across from the HBO and Amazon headquarters. “It was beautiful and festive, an almost party-like atmosphere,” Drohan says. “We’re having fun; we’re going to dance and sing and bring our children. But at the same time, everybody is so serious.”

Alongside the Guild marched representatives from an incredible variety of unions – retail workers, teachers, Teamsters. “We are all here together for a reason,” says Drohan. “I, as a teacher, back your union, and you as a writer, back flight attendants and flight attendants’ unions back auto workers. We all have the same goal; to survive in an economy that is increasingly difficult to do.”

Ultimately, the strike is just one in a “Hot Labor Summer” that signifies deeper undercurrents of discontent surrounding the United States’s gaping wealth chasm. “The gap has been massive since the early 2000s – why now?” says Drohan. “Well, with COVID, we really saw the stark difference between the experiences of wealthy people, working-class people and people of color. I think we’re really coming to a reckoning about what that gap means and what the needs of people are.” Although celebrities are supporting their fellow WGA members, they don’t constitute the majority. And although writers are defending intellectual property rather than material goods, it’s nevertheless a capital and labor dispute. “As working people in this country, there are capitalist structures designed to keep the people at the top at the top, and the people at the bottom at the bottom,” says Drohan. “The vast, vast majority of people are working or middle-class actors and writers who are struggling for every job they get.”

In addition to the WGA, SAG-AFTRA (The Screen Actors Guild and American Federation of Television and Radio Artists) has been on strike since July 14. As of August 11, the combined strikes had cost the state of California $3 billion in lost revenue. The halted productions are affecting not only writers and actors, but a number of businesses throughout the region, such as caterers, makeup artists and dry cleaners. “Studios are blaming the writers and the actors for the impact on the state. But the writers and actors are just asking for a fair contract,” says Drohan.

Although it’s been delayed thus far, audiences will begin to notice significant changes in their viewing selection this fall. Typically, television shows begin production around Memorial Day weekend for a fall premiere date. Talk shows are already at a standstill; expect a lot of reality TV to come.

The Writers Guild rejected a counteroffer from producers on August 22, however, they are expected to resume negotiations soon. Many speculate that studios are attempting to prolong the strike until writers can no longer afford to continue. “Someone said, ‘All we have to do is wait six months until they start losing their houses.’ And that’s what’s happening. People are losing their houses. These are real life human beings, not spoiled, coddled, wealthy people who are sitting on their billion-dollar yachts making $75,000 an hour. Those are the studio executives who are waiting for people like my friends to lose their houses.” Nevertheless, while they may not achieve all of their demands, Drohan says, “The Writer’s Guild has never lost a strike, and they’re not going to lose this one.”