Fieldston News Editors’ Note: This is the second in a series of articles by Daniel Lee about the post-colonial world.

Contemporary Malagasy music is the culmination of a wide variety of musical styles; in fact, many musicians themselves do not consider terms such as “traditional” or “popular” to be suitable to describe their work. The foundation of Malagasy music-creation is embodied by the concept of lova-tsofina, meaning “heritage” and “ear.” Essentially, Malagasy musicians use their ears as an instrument for intercultural communication and exchange–embracing new musical forms while maintaining many of their own traditions.

In the modern era, Malagasy music has changed significantly due to French colonialism, Christian missionization, and other major social changes in the African continent. Older indigenous musical styles interact with imported styles including French variété, Western classical music, pop and rock styles, military band music, Christian church music, and African popular styles. Malagasy music shares a similar instrumentation and musical style, including male or male and female vocals, plucked stringed instruments, electric bass, jazz drums, indigenous drums, and idiophonic percussion. Most pieces are set in a 12/8 or 6/8 salegy meter with a forceful and dynamic rhythm. The harmonic basis lies in the diatonic scale with different combinations of the tonic, sub-dominant, and dominant chords, a reflection of both Western musical influence and indigenous practices. The lyrics of Malagasy music are equally significant; they often express nostalgic views on rural life as well as discourse regarding problems about modern social transitions.

The goal of this playlist was to represent the history, culture, and politics of Madagascar from 1945 to 2023 through a selection of ten songs. In 1883, France invaded Madagascar and by 1896 had established rule over the island. While the Malagasy had two major uprisings against the French in 1918 and 1947, it was not until June 26, 1960 that the country gained independence. Despite beginning to prosper as an independent state, many of the problems which colonialism had brought to the country persisted. By the 1970s, neo-colonialism brought about the end of the Tsiranana government, and a new ruler, Gabriel Ramananantsoa, came into power. Ramananantsoa introduced socialism to the country, which proved to be disastrous. In 1975, he was replaced by Didier Ratsiraka, who continued to bestow socialist policies until 1991 that left Madagascar even more impoverished. Finally, in the mid-1990s, Madagascar abandoned socialism and the economy began to recover, yet the effects of those policies are still felt today.

The Selection:

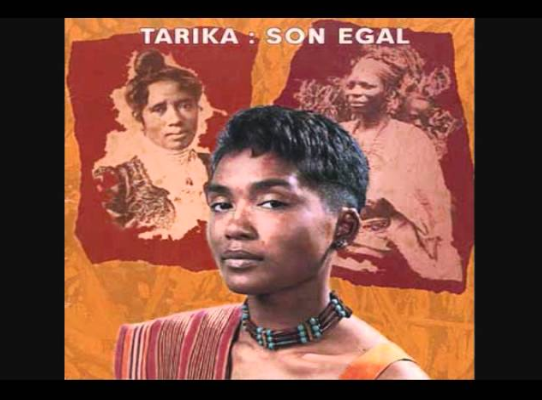

- Sonegaly by Tarika [1997]

“Sonegaly” is the 5th song in the album Son Egal from the popular band Tarika. It was released in 1997 and topped World Music charts across the globe. Since 1993, Tarika have become largely successful and are widely known as Madagascar’s biggest musical export. The band consists of 5 members, led by singer and percussionist Hanitra Rasoanaivo. Lyrically, the band addressed issues that were often neglected in Madagascar. “Sonegaly” and other songs in the album deal with the pro-independence Malagasy Uprising of 1947, which caused the deaths of nearly 100,000 people. On March 29, 1947, Malagasy nationalists started a revolt to overthrow the French colonial powers. The insurrection quickly spread to over one-third of the country. In response, the French not only employed elite forces from the Foreign Legion, but also brought thousands of African soldiers under the command of Senegal to fight the rebels. The French military were extremely brutal, carrying out mass executions, rape, torture, and burning villagers. Finally, the rebellion ended in 1948.

The name “Sonegaly” refers to the Senegalese, who have been demonized after the events of 1947. Although they were trained in Senegal, the troops came from colonies under French control; the soldiers simply acted under orders. One of the lyrics of the song reads, “Do you think we blacks should fight against each other too?” Essentially, the song and the album as a whole serve as a plea for reconciliation between the Malagasy and the Senegalese. “Sonegaly” opens with a variety string instruments–jejy voatavo, a double-sided harp with a calabash resonator; a vahila, similar to a harp; a marovanny, a box zither; and a kabosy, a four-stringed guitar–all under a rhythmic bassline. It then transitions into the vocals of Hanitra Rasoanaivo, and follows a similar alternating pattern between vocals and plucked runs.

- Malaso by Regis Gizavo [1995]

Over the past few decades, poverty in Madagascar has created very difficult conditions for the Malagasy, particularly in the poorer region of the south. Most Malagasy people work in agriculture and produce cash crops, such as coffee or vanilla. However, these jobs are quite unstable because the land is vulnerable to various natural disasters. The island’s poverty has largely stemmed from its fragile economy and government. Since 1960, the country has struggled to find its footing and maintain a stable societal structure. “Malaso” by Regis Gizavo alludes to the ways in which corruption and crime complicate the lives of cattle herders. One of the lyrics reads, “Tsy liñinay matoa zahay mitaray”, meaning “We are not alone because we are together.” It’s a song of resistance and unification and features Gizavo’s accordion-playing alongside male vocals.

- Tsy Miraharaha by Mahaleo [2008]

The band Mahaleo addresses a number of major social and political issues in Madagascar. Mahaleo was born out of the 1972 rebellion against neo-colonial regimes during a wave of protests known as the Rotaka. Overtime, their music became representative of youth protests. In their live performances, the band has created a distinctly communal spirit whereby they and their audiences are co-performers, celebrating and singing together. Their songs reflect this and often include polyphonic singing and multi-rhythmic clapping. “Tsy Miraharaha” addresses the disconnect between Malagasy politicians and ordinary citizens and encourages people to vote and let their voice be heard. The phrase “Tsy Miraharaha” means “I don’t care”, which gives the song a certain ironic meaning. During their performances of the song, Dama Mahaleo, the leader of the band, portrays himself as both a politician and a citizen, bridging the gap between the common people and the elite. He writes this song to remind the Malagasy that one cannot be a member of the Parliament without also being part of the people.

- Antandroy gorodora (accordion) by Very Soa and Magnampy Soa [1994]

Magnampy and Vera Soa are twin brothers who live with their families at the bazary be, the main market in Tamatave. They are both highly accomplished accordionists who have repurposed and retuned the colonial instrument to reflect an Antandroy acoustic aesthetic (originating from the southernmost region in Madagascar). In this song, Vera Soa can be heard offering various tsodrano (blessings) to the razana (a collection of ancestral spirits) while playing the accordion. He greets these spirits formally and requests good health for the future, referencing his havana (kin) in his ancestral homeland in the south. “Antandroy gorodora” is a short segment of music typically performed in a traditional Antandroy tromba spirit possession ceremony. One would commonly hear accordions and vahilas. This piece reflects the Malagasy’s strong belief in ancestral powers which they believe are capable of healing illnesses, solving problems, and healing wounds. It is believed that if these spirits are not appeased with music, they will not take form.

- Antandroy a capella singing by Tompezolo, Avisoa, Famboara, Solo, and Velontsoro [1994]

This piece belongs to the “healing song genre”, whose lyrics are largely improvised in a joking nature. The continuous throat-breathing is a technique known as ndrimotra, which is derived from a word meaning “to heal.” It resembles vocal maresaka–a dense layering of varied songs interacting simultaneously. Typically, the singers are seated on the floor, and one can hear the performers rhythmically banging their knees against the ground to create a more distinctive maresaka effect. One of the female singers in this arrangement, Tompezolo, serves as the tromba spirit medium. Overall, this piece truly highlights the diversity of Malagasy musical techniques.

- Betsimisaraka morceaux tromba: Volamena and Volon’aomby by Jily and Ron Emoff [1994]

This piece is an example of bases, the popular Betsimisaraka ceremonial genre (the 2nd largest ethnic group in Madagascar) based in part upon a 6/8 meter. In Madagascar, however, the rhythm is considered to be a synthesis of double, triple, and compound meters. Each beat is played by the kaiamba shaker and an accordion. Volamena means “gold”, and Volon’aomby refers to a “cow’s hair”, symbolizing the sacred value of cattle to the Betsimisaraka people.

For many generations, zebu cattle have symbolized power and prosperity in Madagascar. Almost all zebus are owned by individual families, and they serve as a sign of wealth and prestige. They also play a key role in a variety of religious ceremonies. However, in recent years, illegal exports, disease, and food shortages have contributed to declining cattle populations. Thus, rebuilding the cattle industry could help restore economic stability in the island and promote trade both within and outside of Madagascar. This song in particular aims to raise awareness of this crisis and highlight the significance of the cattle to the Malagasy as a whole.

- Malagasy by Eusèbe Jaojoby [2004]

Jaojoby was one of the first to sing salegy–Malagasy dance music. He created the modern genre while performing in villages and celebrations, inspired by traditional styles and instruments. As he gained more popularity on the island, he decided to take on a political role and began working for the UNFPA (United Nations Population Fund) as goodwill ambassador. Jaojoby also performed at various political rallies leading up to the December 2001 presidential elections. This electoral standoff triggered months of public strikes and mass protests and nearly caused the secession of half of the country. Just before he announced his departure from Malagasy politics, Jaojoby released his album, “Malagasy”, which was an open call for peace and reconciliation. In this title track, he urges his listeners to look ahead to Madagascar’s future and fight for changes to improve their lifestyles. Jaojoby considers the piece to be his own “personal tribute” to all the people who stood up and advocated for democracy.

- Tovovavy Jerijefy by Rakoto Frah [1988]

Rakoto Frah is known as the undisputed elder and master of the sodina, the Malagasy traditional end-blown flute. Most of his music is based in the Merina traditions of the Central Highlands of Madagascar–in particular, two distinct styles: one derived from the famadihana exhumation and reburial ceremonies, and the other from hiragasy, a type of theatrical performance. Famadihana ceremonies feature both sodina and amponga players. They are infused with fast and energetic music to honor the Malagasy’s ancestry. Accordingly, the famadihana featured in this piece is virtuosic, brash, and full of energy. “Tovovavy Jerifefy” also features a sodina and a kaobsy, a small guitar-like instrument with four to six strings and partial frets. Similar to many other Malagasy songs of the time, it was resemblant of ceremonial music that was reflective of the Malagasy’s spiritual beliefs.

- Taranaka Afara by Razia Said [2014]

“Taranaka Afara” is the opening song of the album “Akory”, meaning “What Now?” Razia Said, a musician and environmental activist, uses this album to impart a crucial message to her listeners: to save Africa from ecological destruction. Her work focuses on restoring Madagascar’s rainforests and protecting its biodiversity. The upbeat rhythm of her music featuring accordions, acoustic guitars, lutes, and vahilas contrasts with her harsh lyrics. The name of this piece translates to “Descendants of Afar.” The song serves as a “call to action” and spreads awareness about the dire state of Madagascar’s ecosystems. It portrays the funeral of a tree and considers what might go through its mind when it’s being buried. The lyrics (in Malagasy) read, “Those who want to rebuild, need to be strong/It will impoverish us, no exception/I’m going to take it easy/Get out of here/ It’s a land of patience/There are no legs to work on.”

- Prezida by Jaojoby [2012]

“Prezida” was a direct address to the president of Madagascar, Andry Rajoelina. In the lyrics of the song, Jaojoby states that if he was the president, he would send soldiers to fight the “real enemy”–brush fires, drought, and deforestation. These phenomena make the land barren and uncultivable, leading to famine. In an interview with Afropop, a public multimedia platform dedicated to music from Africa and the African diaspora, Jaojoby argues that “the worst enemies of human beings, and of all animals, is hunger. If you can’t eat, you lose your head. You make war, violence, you go into prostitution.” Indeed, from 1980 to 2010, 53 natural hazards were recorded–including droughts, earthquakes, epidemics, floods, and more–costing over $1 billion in damages. High poverty rates and a lack of functional institutions left the country more vulnerable to these disasters. This piece is just one example of the political focus of Malagasy music, and its use as a medium for social protests.

Bibliography

Africa.com. “Boosting Madagascar’s Economy by Rebuilding the Zebu Cattle Industry.”, January 20, 2021. https://www.africa.com/boosting-madagascars-economy-by-rebuilding-the-zebu-cattle-industry/#:~:text=For%20generations%2C%20zebu%20cattle%20have,the%20country’s%20coat%20of%20arms.

Afropop. “WAKE UP MADAGASCAR: Jaojoby, Razia and More Tour US to Save Forests” July 11, 2012. https://afropop.org/articles/wake-up-madasgascar-jaojoby-razia-and-more-tour-us-to-save-forests.

Bandcamp. “Taranaka Afara.” Accessed April 2, 2023. https://razia2.bandcamp.com/track/taranaka-afara.

Borgen Project. “Poverty in Madagascar,” March 22, 2019. https://borgenproject.org/tag/poverty-in-madagascar/#:~:text=Poverty%20in%20Madagascar%20is%20complex,improved%20access%20to%20clean%20water.

Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy in Africa. “Madagascar: 2001 Presidential election dispute.” June 2010. https://www.eisa.org/wep/mad2001background.htm.

Frah, Rakoto. “Flute Master of Madagascar.” The Magazine for Traditional Music Throughout the World. Accessed April 2, 2023. https://www.mustrad.org.uk/reviews/rakoto.htm.

Fuhr, Jenny. Experiencing Rhythm: Contemporary Malagasy Music and Identity. Cambridge Scholars, 2013.

Kaye, Andrew. Ethnomusicology 36, no. 2 (1992): 297–99. https://doi.org/10.2307/851929. Leonard, Charles.“Political songs | Sonegaly – Tarika.” New Frame. April 26, 2019. https://www.newframe.com/political-songs-sonegaly-tarika/.

Livingstone, Sonia Livingstone. Audiences and Publics: When Cultural Engagement Matters for the Public Sphere. Intellect Books, 2005.

Margrave, Christie. “Malagasy Ecopoetics: The Hybrid Poetry of Parny, Rabearivelo and Mahaleo.” University of East Anglia. Accessed April 2, 2023. https://ueaeprints.uea.ac.uk/id/eprint/85998/1/JRS_PAPER_An_Ecopoetics_of_Madagascar_EDIT_JF_copyedited_finalized.pdf.

Meinhof, Ulrike. “Madagascar in the World: Songs for Madagascar.” University of Southampton. September 2017. https://heritage-research.org/case-studies/madagascar-world-songs-madagascar/.

Nickson, Chris. “Tarika,.” All Music. 2023. https://www.allmusic.com/artist/tarika-mn0000012425/biography.

RFI Music. “Jaojoby.” February 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/2012021001454/http://www.rfimusic.com/artist/world-music/jaojoby/biography.

RFI Music. “Jaojoby at the Thau Festival” July 20th, 2004. https://web.archive.org/web/20120217001454/http://www.rfimusic.com/artist/world-music/jaojoby/biography.

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. “Madagascar: Spirit Music from the Tamatave Region.” 2001. https://folkways.si.edu/madagascar-spirit-music-from-the-tamatave-region/world/music/album/smithsonian.

Wild Madagascar. “A Historical Timeline for Madagascar.” 2020. https://www.wildmadagascar.org/kids/05-history.html.

WorldBank. “Madagascar.” 2021. https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/madagascar/vulnerability.