In her debut Neruda on the Park, Dominican-American author Cleyvis Natera paints an expansive and ambitious portrait of life in a rapidly gentrifying neighborhood. It feels like New York City but it can really be anywhere. Natera’s direct, no-frills prose allows her to tackle a multitude of important topics in what is a slim, powerful volume.

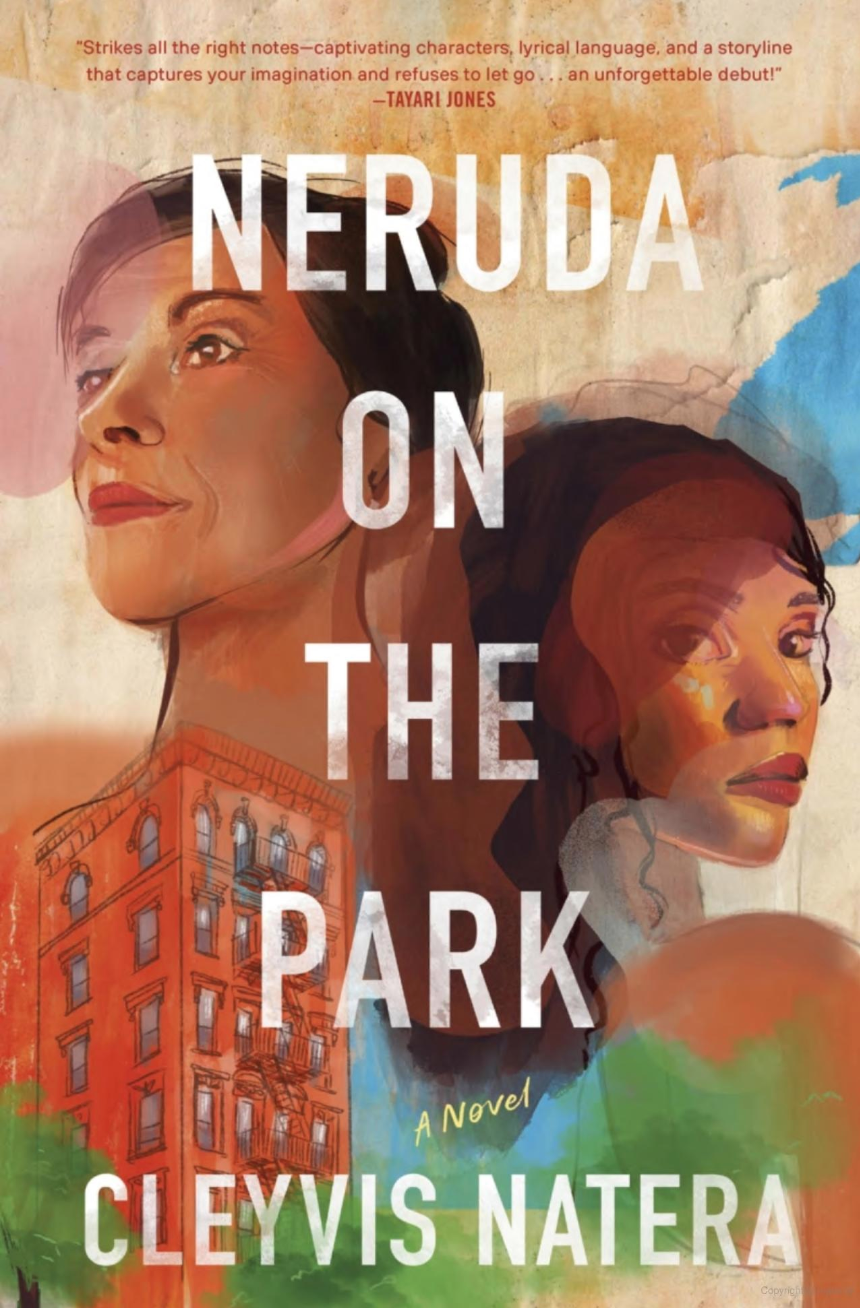

Neruda in the Park may feature a playful, bright cover, but the issues to which Natera speaks are anything but. Neruda tells the story primarily of Luz, a young lawyer – and like Natera, a Dominican emigre – who struggles to reconcile the facts of her elite Ivy League education and offer of a job at a prestigious firm with her home life. Luz and her family live in the fictional Nothar Park neighborhood: development is encroaching on this traditional Dominican enclave. Natera, through Luz, must resolve the conflicts of family and heritage in what is a rapidly changing environment. Complicating matters further, Luz enters a romantic relationship with the nouveau riche developer, Hudson, behind much of the change in Nothar Park. As a character, Hudson is typical of the novel. Though he suffers from the Veblenian excesses that one might stereotypically associate with such a figure, Natera takes pains to introduce nuance into Hudson’s personality: he is an environmentalist who has at least a feel for the plight of long-standing Nothar Park residents. That is to say: even if the characters within Neruda are perhaps not fully fresh – shaped as they are by current events and Natera’s experience – they are at least complex. Despite its place as a brisk, approachable portrait – of love across boundaries, race and economic development – Neruda on the Park is not always a simple book, nor does it often patronize. It does not overemphasize left-right politics, as many books relating to social justice do, but rather frames two approaches – Luz’s complacency and her mother’s nefarious scheming – within the same field of view. This is one of its stronger and more unique qualities.

As Natera shared with the Upper School at a recent assembly, much of Neruda on the Park is drawn from the author’s personal experience of the issues at play in the novel. Natera expounded in particular on her views on gentrification, the book’s overarching theme, explaining that while she did not stand against what she termed “progress,” Natera considered that a firm commitment to ethics – for instance, payouts to existing residents – was needed. Perhaps the author’s words were especially powerful because of their setting. New York, as James Baldwin wrote, is “spitefully incoherent,” a quality not just evident in its world-famous (if rather headache-inducing) tourist areas, but in its past (Seneca Village and Robert Moses come to mind) and the present phenomena of gentrification and redevelopment (think of the South Bronx).

Though those students who read Neruda on the Park, and indeed those who attended the assembly, will have been struck by the writer’s candor in covering her chosen topics (“helpless people are squashed daily…”), they may too have considered Natera’s reflections incomplete. Perspectives on class, race, and gentrification are important, but they are by no means new, nor can Natera’s work be considered the most authoritative on these subjects. The work of James Baldwin, for instance, possesses some of the same bildungsroman-esque self-reflection as Natera’s, but with a more descriptive flair and greater literary pedigree. Jane Jacobs, though her work perhaps is not so timely, also explores issues of urban wealth and gentrification, especially with regards to race (and does so with surgical precision). And no writer, of course, ever has painted finer pictures of love across social borders than Shakespeare. Interested students should strongly consider these authors if they wish to further explore the themes presented in Natera’s writing, which on occasion leaves one itching for rather deeper prognostications and recollections.