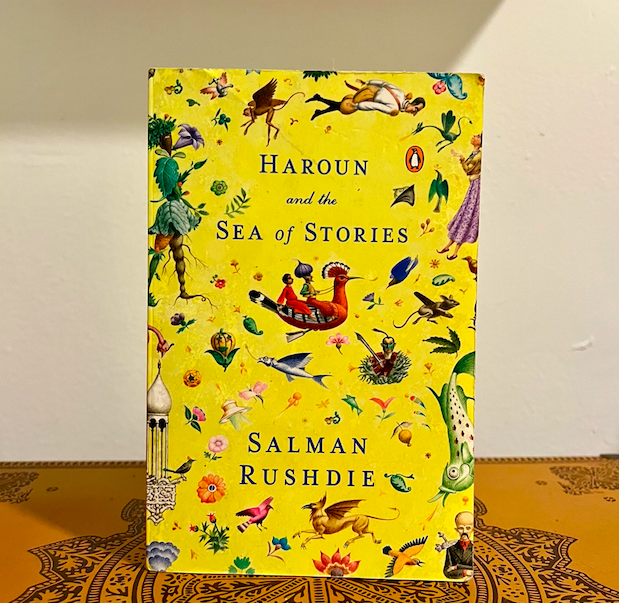

Pictured Above: My first, personal copy of “Haroun and the Sea of Stories”

I was in 6th Grade when I first read “Haroun and the Sea of Stories”, recommended to me by my mother who took a ‘life changing’ class on Rushdie’s work in college. It’s a beautiful book written in exile, in hiding, by a man with a fatwa hanging over his head. I didn’t know that at the time. At face value, it was the most fantastical, dazzling and inventive story I had ever read. Upon a second reading, in high school, and with a deep explication of the politics that undergird Rushdie’s immense literary significance and cultural capital, ( again, by my mother), I fell deeper in love with the novel’s “new” meaning and admired its layered consequence as a social commentary and an act of fierce rebellion. Rushdie is one of the greatest contemporary examples of activist literature. He is someone who ingeniously defends what should be the universal ideal of freedom of expression and takes heroic risks through his storytelling to do so. His work is an unmatched risk in itself, and catalyzes international conversations in a manner that is reminiscent of writers like Voltaire, Harriet Beecher Stowe and Chinua Achebe. He makes you aware that being stabbed nearly to death is sometimes the price of having your books published.

Rushdie is currently in the hospital after being stabbed repeatedly while he was on stage at the Chautauqua Institution in upstate New York decades after the fatwa was decreed. He has wounds to the neck, stomach and liver, with severed nerves in one of his arms. He spent several days on a ventilator. According to his literary agent, Andrew Wylie, he will likely lose an eye. Rushdie, a soaring symbol for literary prowess and daring artistry has suddenly become a human, who is suffering tremendously.

It will be thirty four years next month, on September 26, since “The Satanic Verses” will have been published. It will be thirty three years this upcoming year, on February 14, since Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa ruling that Rushdie shall be killed. This religious edict was due to the ‘blasphomeous’ representation of the Prophet Muhammad and Islam. In the early years of the fatwa, deadly riots and bookstore terrorist attacks occured internationally. Several of Rushdie’s translators and publishers were targeted and attacked; one of which, a Japanese professor of Arabic and Persian literature, and translator for Rushdie, Hitoshi Igarashi was stabbed to death.

With a three million dollar bounty offered for his murder, the author went into hiding for over a decade, only recently reentering the public sphere. He chronicled this dizzying, dislocating period of his life in the 2012 memoir, “Joseph Anton.” Over time, and through international agreements, Rushdie was able to travel more freely.

One can only imagine the personal and professional implications of this infamous ‘Rushdie affair’ on the writer. Rushdie has published eight novels since “The Satanic Verses.” His work covers an impressive breadth of genres ranging from children’s fiction to memoir and nonfiction. He has shown confidently forceful and shockingly self aware humor in recent years at public appearances. In a family statement in the aftermath of the attack, his son said: “Though his life changing injuries are severe, his usual feisty and defiant sense of humour remains intact.”

Rushdie has traveled near and far from his new home to give lectures and participate in events, speaking on so much more than the subject of the fatwa. Friday’s attack has put that aspect of his identity at the forefront of the public’s mind once again. It’s up to us on how we choose as a society to help him heal from this tragedy as an artist and a person.

Despite what you think about Bezos, it certainly sends the right message to despots and zealots that “The Satanic Verses” has climbed close to the top of Amazon’s bestsellers in literature and fiction this past weekend. The demand for such a piece of literature, economically and intellectually, speaks to a larger social resistance that is essential to fight for freedom of expression. Rushdie’s work brings the loftiest goals of literature into existence. It contextualizes our current movement, and showcases how narrative and story create routes to resistance of oppression and serve as checks on power. This is done by using what Dr. Cornel West called using our ‘roots’ to ‘help determine our routes.’ In a lecture at MIT on the topic of Institutional Provincialism, he describes “All of us are thrown into time and space under provincial circumstances…and we have to be rooted in that provinciality and have the courage…(to) dig deep enough to find the universality in those roots.” Demand for this kind of work, showcases that courageous literature that dares to achieve the former still has a place in our world.

Freedom of expression matters. America has collectively failed Mr. Rushdie and artists around the world by allowing such a direct, tragic attack to occur on our soil. As Margaret Atwood said in a recent Op-Ed for The Guardian, “American democracy is under threat as never before: the attempted assasination of a writer is just one more symptom.” Rushdie never missed the opportunity to speak out in his personal life on the principles he so expertly embodied in his writing life. Freedom of expression was key among these which came through by his tenacious work with organizations like PEN America and his signature on the 2020 Harpers Bazaar letter coming to the defense of free and open debate. “The free exchange of information and ideas,” the letter states, “the lifeblood of a liberal society, is daily becoming more constricted…if we won’t defend the very thing on which our work depends, we shouldn’t expect the public or the state to defend it for us.”

The world should have rallied behind Rushdie when the threat presented itself over three decades ago. It should sadden us all that we opted for what The Atlantic’s Graeme Wood called “the cult of offense” instead. The term refers to a considerable sect of the public who are of the opinion that while they condemn murder, Rushdie should have been more attuned to the sensitivities of ‘the offended’. This cultural phenomena was cultivated by Jimmy Carter’s 1989 Op-Ed in The New York Times which lamented that the west has promoted a book that “is a direct insult to those millions of Moslems whose sacred beliefs have been violated.”It should sadden us all that it took life threatening circumstances to get an outward defense from politicians and figureheads at home and abroad.

If there were any remaining doubts about the pressing, undying significance of freedom of expression, allow Rushdie to be a testament to that truth. Also, allow him to be more than the heroic free speech titan he is. Don’t only share the stories of his attack in a fleeting frenzy. Read the complete works of Salman Rushdie. Read the works of other banned writers. Continue to read a diversity of work by a diverse set of writers – in every sense of the word.

Fieldston, as an educational institution, has a responsibility to be an essential worker in the fight for the principles Rushdie epitomizes. My fear is, we let the Rushdies of the world slip through our fingers.

Thank you for covering this important and timely issue. It is unfortunate that you had to write about Rushdie in the context of this heinous attack but it’s a result of him “walking the walk” and not just paying lip service in the fight for freedom of speech. Sadly, your final reflection is a possibility when people are afraid to challenge oligarchy’s and and other systems of power. It is a call your generation is tasked with, to ensure that freedom is upheld for all people.