It is no secret that opera has historically struggled with a lack of racial diversity. In a recent study by Opera America, an organization that works with opera companies, it was found that only 20% of administrative employees at opera companies in the United States and Canada identify as people of color. For reference, people of color constitute 39% of the general population. The Metropolitan Opera, the largest opera house in the United States, exemplifies the problem. As of 2020, only three out of its 45 board members and two out of its 100 orchestra members were Black.

This issue was brought to light in the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd in 2020. Since then, Black artists have increasingly spoken out about their experiences with racism and discrimination. “In 20 years, I’ve never been hired by a Black person,” said renowned bass Morris Robinson. “I’ve never been directed by a Black person; I’ve never had a Black C.E.O. of a company; I’ve never had a Black president of the board; I’ve never had a Black conductor. I don’t even have Black stage managers. None, not ever, for 20 years.” Other Black singers such as tenor Lawrence Brownlee and mezzo-soprano J’Nai Bridges noted that they have shared similar experiences.

The problem extends beyond diversity in the workplace. There is also very little diversity in the repertoire performed in major opera houses. For instance, up until last year, the Metropolitan Opera had never performed an opera by a Black composer. Granted, it is true that the bulk of the established operatic canon is European and thus composed by white people; however, this does not mean that Black composers’ work should not be given a chance.

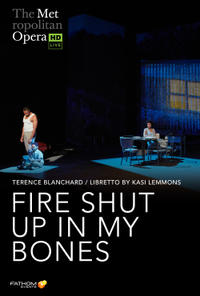

Opera houses have begun making an effort to reverse this scarred image and reestablish the opera world as an inclusive and welcoming place. In 2021, the Metropolitan Opera premiered a new opera by Terrence Blanchard, Fire Shut Up in my Bones, the first opera by a composer of color in the organization’s history. It turned out to be one of the season’s highlights, with most performances selling out. In 2023, the Met will stage another opera by Blanchard, Champion. Furthermore, the Met recently presented a season-long exhibition, Black Voices at the Met, which, in the words of General Manager Peter Gelb, “explored the company’s fraught history engaging African American artists and the long journey toward racial equality in the opera house”. Alongside the exhibition, the Met also released a CD, Black Voices Rise, featuring performances by singers including Robert McFerrin, Jessye Norman, Kathleen Battle and other Black artists whose profound voices shattered opera’s once impenetrable color barrier.

It was only sixty-seven years ago that contralto Marian Anderson made her debut at the Met, becoming the first Black singer to do so. Since then, opera has undoubtedly made immense strides toward ridding itself of prejudice and racism. The effort cannot end here, however, as there is still a lot of progress to be made. Opera companies must continue increasing the diversity of their casts and orchestras and expanding their repertoires.

Here is a collection of some of my favorite recordings by singers of color, some drawn from the Met’s Black Voices Rise CD and others that I selected myself:

Richard Wagner – “Liebestod” from Tristan und Isolde

Giuseppe Verdi – “O patria mia” from Aida

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – “Deh, vieni, non tardar” from Le Nozze di Figaro

George Gershwin – “Bess, you is my woman now” from Porgy and Bess