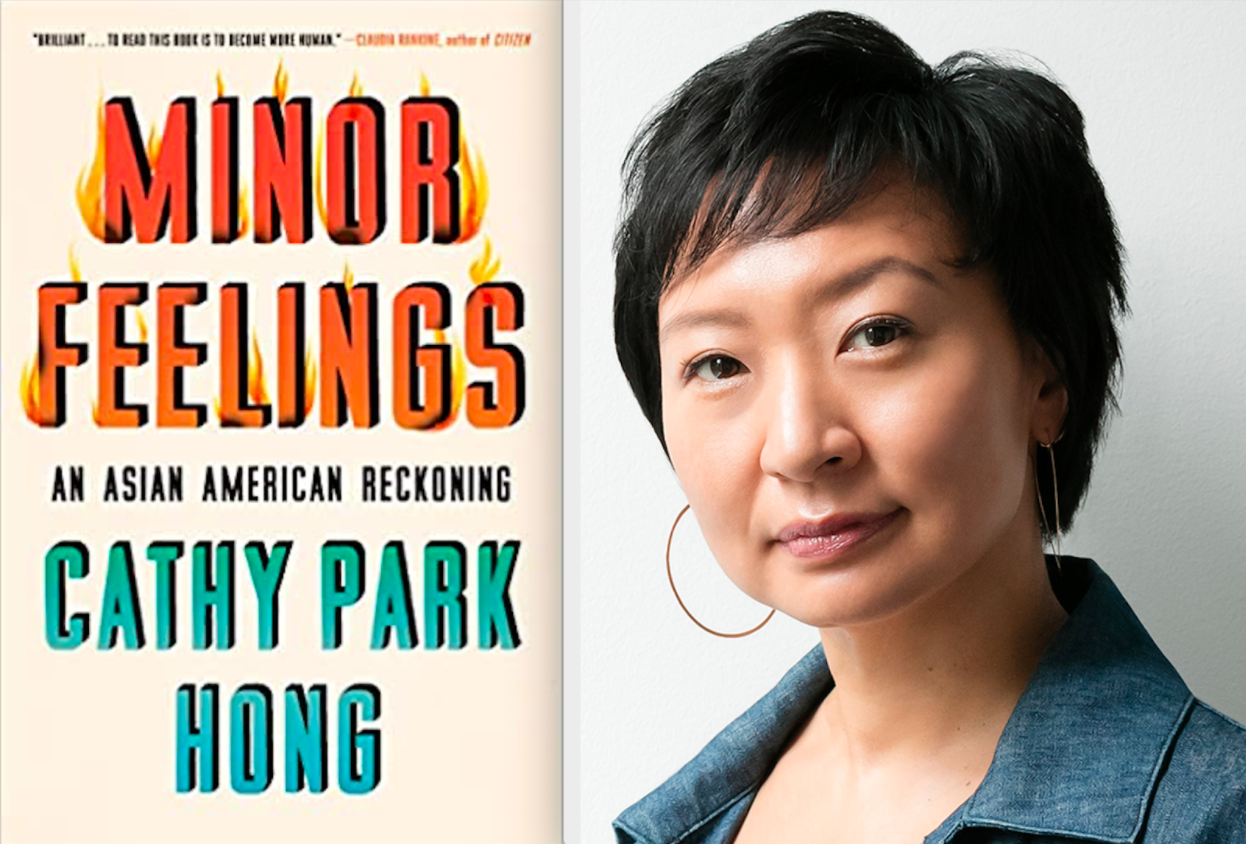

In Minor Feelings, Korean-American poet Cathy Park Hong tells the raw and unfiltered Asian-American story. Throughout this collection of essays–which are both heartbreaking and beautiful at the same time–Hong is a voice for a community that so desperately needs to be heard. And while each essay is devastating, the collection is a sort of beacon of hope for the Asian-American community. It is an opportunity to be heard; to be acknowledged.

Upper School DEI Coordinator Arhm Wild read Minor Feelings right when it came out in hardcover. “It is an incredible feeling to read a book and feel like it is somehow able to articulate feelings that I’ve had my whole life but have never been able to name. There is such validation and elation in seeing your experience written about so clearly, as if finally learning a language you’ve been trying your whole life to speak. As one of the only books I know that talks explicitly about the racialized experiences of Asian-Americans, the book feels critical in creating our ability to talk about race, the pressures of assimilation that underpin silence, and the greater systems of inequity and racism that our experiences fall within. I am also deeply inspired by the ways that this book clearly names the prejudice, bias, and colorism in our community as this naming is the only way to move the dial on anti-racism work,” Wild said.

Before publishing Minor Feelings, Hong was known for her poetry. Her work includes collections such as Engine Empire, Dance Dance Revolution and Translating Mo’um. In spring 2020, Hong published Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning and it gained national recognition quickly, becoming a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and winning the National Book Critics Circle Award for autobiography. Hong was even included in TIME’s Top 100 Most Influential People of 2021 list.

This year, the majority of Fieldston students read either the full text or snippets of Minor Feelings in their English classes. On Tuesday, December 7, Fieldston students had the privilege of hearing Hong speak. Hong spoke two times: once specifically to Asian-American students (organized by ACTIVE), and once to all Fieldston Upper students.

Hong’s talk was set up by English teacher Michael Morse and English Department Chair Alwin Jones. Wild also worked with them to set up a space where Hong could speak specifically to Asian-American students. “It seemed to be a book that had touched the students deeply and a book I personally felt was profound for the Asian-American community and intergroup conversations on race. We were really excited about the opportunity to create an affinity space with the author of such a groundbreaking and important book,” said Wild.

I attended both talks; the first one was the ACTIVE event and the second one was a school-wide event. The first session was led by Wild, who has a personal connection to Hong. “Cathy was my thesis advisor at my MFA Poetry program at Sarah Lawrence. The manuscript I was working on with her, which eventually became my first book, was asking a lot of questions about holding hyphenate identities and navigating belonging in spaces that insisted on some sort of erasure. Cathy was instrumental in creating a clearer sense of purpose, of who I was writing to and for, and a sense of pride in being a queer Korean-American writer writing to other queer and/or Korean-American audiences. Cathy also wrote the blurb to my book, Cut to Bloom, which I’m incredibly honored by,” said Wild.

After giving a brief introduction, Wild went into a list of questions for Hong. The questions were as follows: What’s one piece of advice that you have for other Asian-Americans? What was it like to express the challenges you faced within your identity in essays such as ‘Bad English’? Were you supported and met with others who had like-minded experiences, or did you find the opposite? In your book, you write that it’s difficult for you to write about your mother. How did you grapple with maintaining your family’s privacy while writing your truth in Minor Feelings? Do you have any advice for being Asian-American in PWIs (predominantly white institutions)?

Hong’s responses to these questions were just as profound and touching as her written work. I will always remember how Hong articulated that Asian-Americans can still be heard and take up space while also making space for others.

“A response that really resonated with me was when she was talking about how important it is to find your community and become creative in how you imagine your belonging. As someone who has felt like I don’t always belong in Korean-American spaces because of my queerness or vice versa, it was comforting to hear a reiteration of the importance and possibility of creating community and chosen family,” said Wild.

Angie Wong (V) said, “The talk made me feel like I was heard, especially because Fieldston is a primarily white institution. I especially appreciated Cathy Park Hong’s strong support for young Asian-Americans.”

Hong has become one of my personal heroes–and I know I’m not alone. “Cathy inspires me to be brave and unapologetic while continuing a commitment to understand and consciously unlearn how the pressures of assimilation and being first generation American impacts my ethos, worldview, and sense of self. Her book reminded me that being able to talk specifically about your experience can help connect you with a greater number of people than perhaps you could have imagined. I have heard people from all different backgrounds talk about how they related to this book, and I am inspired by the impacts of talking so bravely, analytically, and clearly about race,” said Wild. Hong’s ability to put a struggle that so often goes unheard into words and to do so with such visceral honesty deserves to be recognized. Hearing Hong speak directly to the small group of Asian-American students at Fieldston was a moment I will never forget. Reading Minor Feelings felt like I was reading my own thoughts on paper, and there were times when I was reading it that I forgot I was reading someone else’s story and not my own. Listening to Hong speak in person further enforced the fact that I am not alone; that other Asian-Americans feel the same things that I feel. On that day, I felt immense pride for my community.