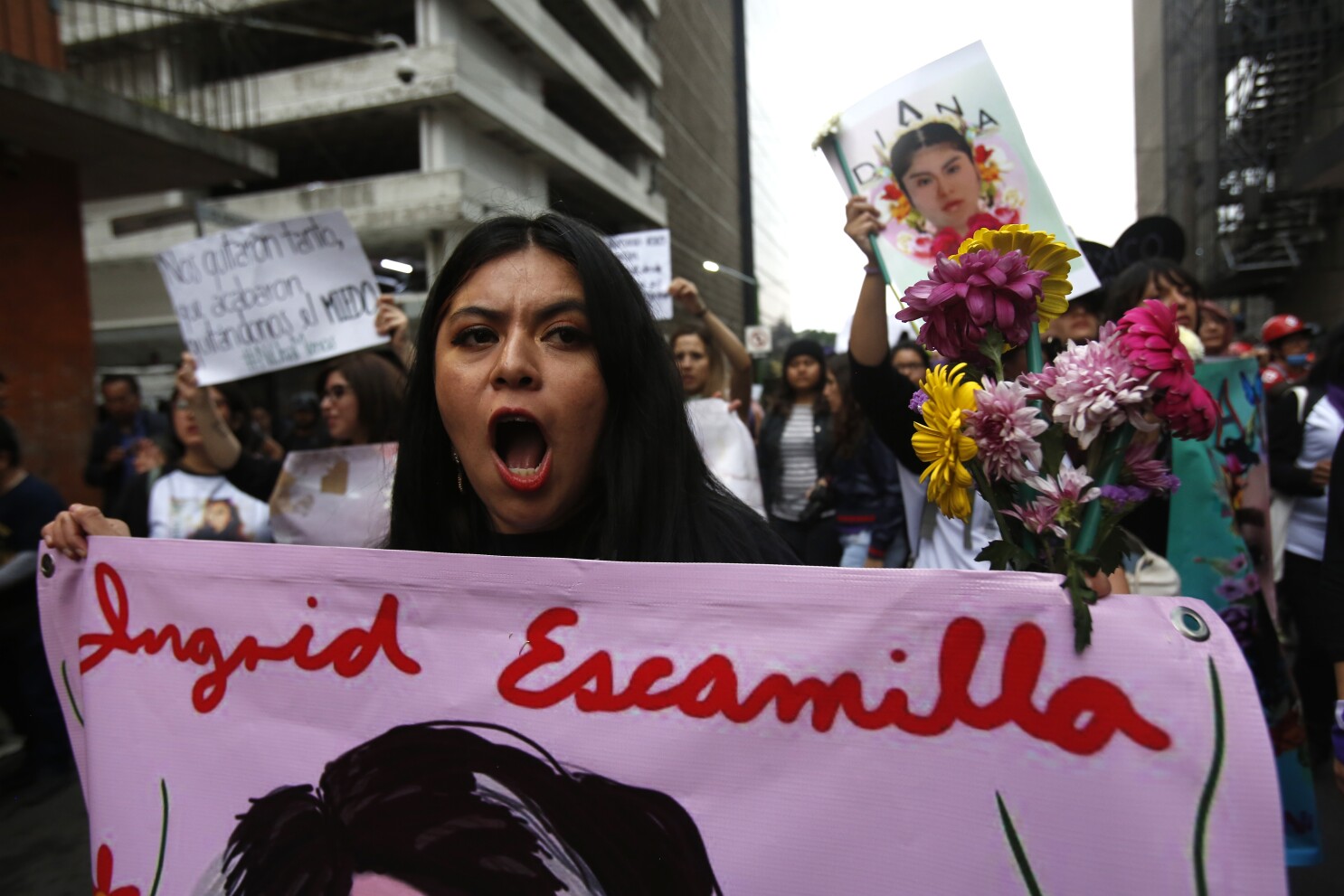

photo credit: Los Angeles Times

Mexico: It is a country where ten women are found dead daily. Their bodies are discarded like trash in public places for all to see their dismembered corpses, to see signs of extreme violence, evidence of sexual assualt, even torture, and yet the authorties continue to fail to protect the female population in Mexico. Not only are these women failed in life, they are also failed in death, as authorities continuously fail to conduct honest and thorough investigations.

Mexico is no stranger to human rights violations, but over the past few decades the war against women has reached astronomical levels. Not one out of thirty two states can report zero “feminicides,”the legal and sociological term used to categorize the killings. The increasing failure by the authorities between 2016 and 2021 is prominent; the attorney general announced that over the past five years, this new wave of killing women increased by a jarring 137%.

In 2009, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights conducted an investigation into the way Mexican authorities handled the brutal murders of three young women in Ciduad Juárez, Mexico. Their report concluded that Mexico failed to properly adopt the necessary measures to carry out the investigations. The Inter-American Court also found the country guilty of failing to do their job to investigate. Therefore, Mexico was also found guilty of violating rights to life, personal integrity and the liberty of victims.

“This judicial ineffectiveness when dealing with individual cases of violence against women encourages an environment of impunity that facilitates and promotes the repetition of acts of violence in general and sends a message that violence against women is tolerated and accepted as part of daily life,” their report states.

Amnesty International compiled a list of common failings identified in investigations across Mexico. Their report identified three main problems among feminicide cases: public servants are losing evidence during ongoing investigations. For example, in certain killings, ropes and shoelaces believed to be the murder weapon were lost; nails were not scrapped to find evidence of self-defense; acid phosphatase tests to determine sexual assault were not performed, etc: authorities do not conduct investigations sufficiently. Crucial lines of the investigation are often not pursued, and necessary steps of procedure are not completed: gender perspective is not applied correctly or at all throughout an investigation. When lines of inquiry are not developed from a gender perspective, feminicides are often investigated as suicides, or those close to the victim are investigated. A lack of gender perspective also leads to victim-blaming, stereotypes and incorrect conclusions.

In 2020, 3,723 women were killed and calls regarding violence against women rose by 30%. Alongside the number of deaths, public outrage and protests are also increasing. On November 4, 2021, the Day of the Dead Women protest was held in Mexico City, the day after Mexico’s Day of the Dead holiday.

Consuelo Martínez lost her daughter, Victoria Pamela, to feminicide, she told Efe news agency that “We really want the authorities to act… We seek justice and truth for each of the dead.”

The protest was a chilling but effective image as women chanted “We are your voice,” while they marched with crosses painted with the names of the dead, banners and images of their lost loved ones.

“Each cross is a case, a pain,” Martínez said.

Despite the cries, tears and begging, the Mexican government continues to neglect the issue. President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) has had an insensitive approach towards the violence against women since the beginning of his presidency. He believes that 90% of phone calls to the police from women about domestic violence are “false.” In May of 2020 he even told reporters that “Mexican women have never been protected as now.” But the facts tell a completely different story from the false narrative he communicates.

The Washington Post quoted AMLO saying “I don’t want feminicides to distract from the raffle,” which further confirms his disinterest in the deaths of his citizens.

Alongside his completely dismissive comments, trust in the Mexican authorities has been dwindling for decades. According to Encuesta Nacional de Victimización y Percepción sobre Seguridad Pública (ENVIPE), in 2015, 93.7% of all crimes were unreported. In 2016 the organization reported that 63% of people did not report crimes for reasons related to authorities. 33% believed that reporting would be a waste of time, 17% did not report because of their distrust in authorities, and 50.4% of those who did report said they received “bad” and “really bad” treatment from the authorities. 45% of the Mexican population reported little or no trust in public figures like judges, police, attorney generals and public ministry, while 64.4% saw them as corrupt.

“I have every right to burn and break. I’m not going to ask anyone for permission, because I am breaking for my daughter,” said protester and broken mother Yesina Zaimuda to a crowd in February 2020. The ineffectiveness of the police and disinterest from the president leaves women with only one choice, to make themselves heard at any cost.

Protests in 2020 reached new highs when activists took over the Federal Human Rights Commission Building in Mexico City. The occupation began September 2, when feminists stormed the building to create a save haven for women and children fleeing all forms of violence.

This action is one of many radical steps taken by Mexican feminists who have grown more confrontational with the rising death toll. Within the building, women have been tearing down paintings of historical figures and defacing them with graffiti. The walls are now covered with the names of rape victims and pictures of women who fell victim to feminicide. For months prior, protestors have been defacing monuments, attacking state attorney general’s office’s and even vandalizing the doors of the National Palace.

“We’re here so that the whole world will know that in Mexico they kill women and nobody does anything about it,” Zaimuda said to reporters.

As thirty people slept in cots and on the floor inside the federal building, women—with the help from feminist organization Ni Una Menos (Not One Less)— created a list of demands. They called for women to protest without prosecution: for police gender sensitivity training: for AMLO to create and share a report on ways to decrease gender-based violence; and for states to guarantee quick and effective resolutions for all feminicide and disappearance investigations.

The president was quick to condemn the women for their vandalism and disregard for past Mexican historical figures. In response to questions about the demonstrations, AMLO called “to abandon violence and demonstrations.”

The president believes that the feminist movement is infiltrated by his opposition, and that the protests are simply orchestrated means to undermine his presidency, “it struck me that, of all the columnists, columnists, only 10 percent were women; In other words, the defenders of women’s rights do not have women in their newspapers and it is becoming increasingly clear that there are people interested in affecting us,” he stated at a press conference.

The president’s ignorance of the severity of the violence is clear, especially since a 2020 government survey reported that 80% of women do not feel safe in Mexico. Only a small 10% of all criminal cases in Mexico result in a conviction, but with women that percentage drops lower. Human rights groups report that only 2% of rapists are jailed.

The World Health Organization stated that approximately half of all women in Mexico will one day experience the horrors of sexual or domestic violence. Unfortunately, many women will experience these crimes more than once.

Ashley Avila’s (V) parents are from Mexico City and Morelos, Mexico. As a young Mexican woman, she is outraged by the president’s ridiculous conspiracy theories. AMLO’s belief that the feminicide protests are just his opposition is “so egotistical of him.” It is not an orchestrated political tactic, Ms. Avila says that “it’s something that needs to be heard; something that needs to be said. He should not be having that type of pride because he has done nothing to earn himself that confidence.”

The president’s response to the issue is unfathomable to her, “At this point, he’s choosing to not see what’s really happening. I don’t understand—I generally don’t understand how he could believe that. It’s completely dismissing their experiences and their trauma. It’s insane.”

Ms. Furfey, is a Spanish Teacher here at Fieldston who has a deep love for Mexico and its culture. In the past twenty years, she says the rising cases of feminicide have sparked a new and unfaltering wave of attention: “The awareness has become obviously much more acute. There have been protests just in the last few years, big protests, the whole movement of Ni Una Mas, and it’s not solving the problem yet.”

The voice that Mexican women have found for themselves is unheard of for the country. As the death toll rises, women’s voices get louder, and Ms. Furfey starts to wonder what role machismo has to play in feminicide because of it. The feminist movement hit Mexico after it reached the United States, “When I see young women going out in the streets and spray painting things and protesting, that’s something that’s never happened before in the country. It’s happened before in the states, but never in Mexico has that happened,” she says.

As Mexican women loosen themselves out from under the grip of men, Ms. Furfey’s curiosity on the subject grows: “I just wonder with the existence of machismo being more intense in Mexico, for example, what that connection is. When women actually start to speak for themselves, and to not be subservient, and to be able to utilize their intelligence publicly and professionally. I wonder if some of this is a black lash.”

As a young Mexican woman, Ms. Avila has first hand experiences with the toxicity of machismo in Hispanic culture. She agrees with Ms. Furfey that the machismo of Hispanic men is a murder weapon: “The machismo that causes a lot of these things, it’s something that as a Hispanic woman you have to deal with a lot in these families. Whenever there’s a reference to toxic masculinity in my family, it gets me one edge because I realize that it’s what leads women in Mexico to their deaths. Obviously, it’s not the only thing but it’s a big part of it.”

From an outside perspective, Ms. Furfey notices—all the way from the states— that the government has an alarming lack of concern. Their response to the feminicides is shameful, “It’s really sad, it’s pathetic, it’s awful. It’s really a shame,” she says. However disappointing the reaction from AMLO and his government is, Ms. Furfey is not surprised, “Obrador is just incredibly disappointing on a lot of things. Specifically his response to this issue has been, he’s not just ignoring it, he’s blatantly defending it or saying that it’s not a big deal, and blaming women for it. That makes me obviously really angry.” Ms. Furfey says that Mexican politics reached a point, long ago, where you just “throw your hands up.”

Ms. Furfey experiences an internal battle on whether she can visit the country she loves so much. Like all countries, Mexico has a scale of extremely dangerous to fairly safe places to go. Even so, for the first time in her life, Ms. Furfey questioned if she could go: “I applied for a Fulbright, to a small town that’s outside of Mexico City, and I was thinking I want to be independent like I am here, but I wonder if that’ll be safe for me to be independent. It’s really the first time I had to pause and think about it.”

Ms. Avila now struggles with a bit of an identity crisis. In conversation with friends, specifically white friends, she has to find a way to balance her cultural pride and bash it. She says, “I’m conflicted between if I want to defend Mexico whenever it comes up, or kind of go against it. Obviously I want to be able to say, ‘yeah I’m Mexican,’ and be proud of that, but I can’t do that when people are talking about all the things happening there. You have to bash it a little bit, but also make it seem like you’re a little bit proud.”

What is even harder for Ms. Avila is how her Mexican identity is that of a minority. She comments that “as a minority, you have to make yourself heard and bring attention to your ethnicity,” but that attention also makes people outside of Mexico realize the unfortunate realities of the country.

Ms. Avila has been to Mexico only once in her life. A number, that to her, will never be enough. However much she longs for her country, she understands her parent’s reasoning; it is simply not safe. The one time that she went, she says she did not feel the impending danger around her: “I was on a high of just being able to see my family, but even though I want to go I still have those thoughts. I don’t know what could happen,” she admits.

With the rise of narcos and feminicides, Mexico’s reputation has been dwindling over the past few decades. Unfortunately, the beautiful and vibrant Mexican culture is overshadowed by the overwhelming amount of violence, and rightfully so. There should be an outcry against feminicides, but for many people, including Ms. Furfey, violence is not the way they want Mexico to be remembered.

Ms. Furfey says that she tries to find a balance between her love for the country and her safety: “I don’t want to think of Mexico as having this reputation of being dangerous, especially for women, and as a place not to go because of this. I think that’s unfair for Mexico. I certainly don’t want to give into that, but the reality is that no, I wouldn’t be walking by myself in the night time in Mexico.”

What is even more painful for Ms. Furfey, is that her daughter cannot visit the country that claims half her ethnicity: “It’s my dream that she does [go to Mexico] and that she’s able to spend time with her family.” Irapuato, Guanajuato, the Mexican state her daughter’s father is from, is simply not safe. Between the violence of the cartels and the war on women she says, “I don’t feel safe right now. I feel very nervous about it, and not just because of feminicide but rather because of narco violence.”

Ms. Avila has learned how to view Mexico from two different perspectives. One that allows her to pridefully claim her identity, and another that lets her see it from the eyes of a woman living in fear: “January 6, with Rosca de Reyes, I was like, ‘wow, I love being Mexican.’ My mom made champurrado and I was like, ‘wow, this is a great time.’ I’m also still able to look at it from a political perspective and be like ‘oh, I hate it here.’ So It’s kind of like, which side I wanna be on for that day.”

There is one question that Ms. Furfey cannot shake, “Who’s doing this?” The feminicide situation has reached such high levels that the entire situation is practically unfathomable. She keeps asking herself, “Is it serial killers like there was in Juárez, and if there was, then how does that account for all the other mass homicides of women in other areas of the country?”

She created a scenario in which she decides to take action, but she got stuck on the first question yet again, she asked again,“Who am I targeting? Meaning who’s doing it? Is it one person, is it a group of people, is it a sickness in the minds of Mexican men, is it narco related, is it all of the above?”

The only people in Mexico with those answers are the murderers themselves, and possibly the authorities. To Ms. Furfey however, there might not be a distinction between the two: “I’m just trying to think if I had a situation would I call the cops? I don’t think I would. Why would you? There’s not only a lack of justice but the amount of corruption like we were talking about before, the idea that it’s real possible that they could be the ones involved. Not just the protection and the payoffs, but the actual involvement.”

While Ms. Avila is not extremely well versed in the issue of corrupt Mexican authorities, the deterioration of Mexico’s integrity is impossible for her to deny. She told me that “from what you hear and what you see over the years, you can see how it’s crumbling, very rapidly—the system.”

She places a majority of the blame on the government’s cowardness against the growing power of the cartels. In Mexico, there are a growing number of ‘dead states.’ These states are essentially overrun by the cartels under the knowledge of the government.

“The government is allowing the drug cartels to basically govern over the whole of Mexico,” she exclaimed angrily.

The power and wealth of the cartels against the poverty of Mexican civilians is unmatched; they get to twist the hands of the Mexican authorities. Ms. Avila says that the corruption among authorities has a direct correlation to money: “They [the cartels and the government] don’t really care about the people unless there’s money involved. So the people that do have money are able to twist the system in whichever way they want. If anything happens against them, they somehow get out of it with whatever money they have.”

The violence and corruption creates a cycle of poverty that pushes people into the hands of cartels. It is a cycle that Ms. Avila resents, “a majority of the people in Mexico don’t have the resources to sufficiently provide for themselves. That can go one of two ways. Either they join cartels to get that money that they need to survive and join the hierarchy that is the cartels, or the people who don’t have money can figure out how to get through life,” but she says there’s “no guarantee that you can survive by yourself.”

Throughout the history of feminicides in Mexico, there is hardly any accountability or justice.

“Do they know who’s doing it and they’re just not brought to justice,” Ms. Furfey asks, “I want to know who it is. There is something very mysterious about it. But does it need to be such a mystery?”

While the government ignores the situation, people like Esther Chávez Cano created organizations to protect women and find the answers to questions like Ms. Furfey’s that the authorities neglect. Esther Chávez Cano was a globally respected human rights activist from Ciudad Juárez. She was a force to be reckoned with, a pioneer in protecting the women of Juárez, and the first to dare demand better investigations into feminicide.

Ciudad Juárez, previously held the title as the most dangerous place in the world. The city has one of the highest murder rates in Mexico; 2021 ended alongside the lives of 1,420 people. In the 1990s the previously small dangers exploded into extreme violence and forever changed the city. It is estimated that between 1993 and 2005, 370 women were killed.

In 1999, Ms. Chávez, my great-aunt, opened Casa Amiga Esther Chávez Cano, a non-profit organization in Ciudad Júarez. The organization originally started in my father’s childhood home, right across the Mexican-US border from El Paso, Texas. His family nicknamed it ‘La casa Perú,’ because of its address, Perú 878, Hidalgo, 32300 Ciudad Juárez.

Since then, Ms. Chávez was able to get her own building and establish her own headquarters in the south of Júarez. Unfortunately, she passed away in 2009, but the organization is still flourishing and establishing branches across Mexico.

Casa Amiga Esther Chávez Cano offers intervention services for women and children experiencing familiar or domestic abuse, which includes: legal assistance, medical assistance, psychological treatment and access to safe-houses. It is the only rape and abuse crisis center in Juárez, despite origionally opening to combat feminicides.

Ms. Chávez’s legacy lives on not only through Casa Amiga’s work, but also through New Mexico State University’s Esther Chávez Cano collection. For thirty years, Ms. Chávez collected newspaper clippings, photos, magazines and anything with information on Juárez’s atrocities. Her personal collection is on display at the University as a memoriam to not only her, but gender-based violence. Until her death on December 25, 2009, she was still keeping track of the missing woman of Juárez. If the police did not know the names of the victims of feminicide, my great aunt certainly did.

In the (translated) words of Ms. Chávez, “We have much work left to do, the road ahead is long and hard. There will come a time when my voice becomes silent so that new voices can be heard to carry on the struggle for the rights of women, which, as I have said, is also for the rights of men, because it is the struggle for a more just and democratic society for all.”

Esther Chávez-Cano on the left, myself in the middle, and my father Enrique Chávez-Arvizo on the right.