Jonathan Mirsky, a well-known historian, journalist and member of the Fieldston class of 1950, died on September 5, 2021 at the age of 88. He popularized the field of modern Chinese and Asian studies and was an outspoken critic of Communist China. He became famous for reporting from the Tiananmen Square uprising in 1989 where he was recognized as a reporter and had his teeth knocked out and his arm broken by the Chinese police.

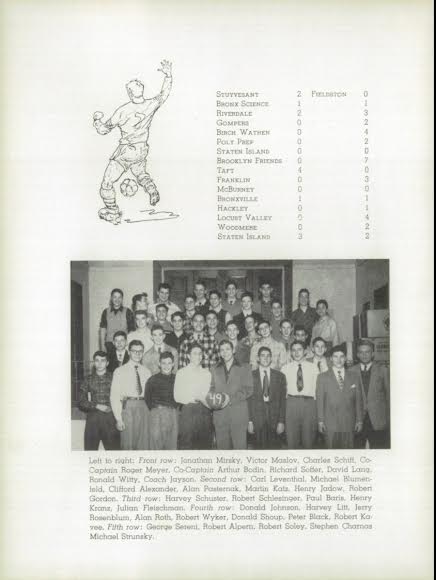

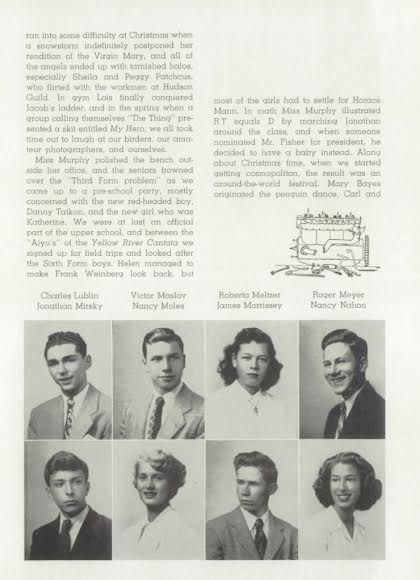

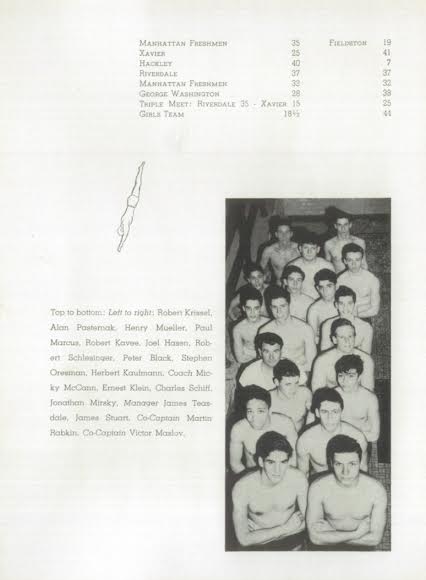

What the many articles that have been written about Mirksy’s life and accomplishments leave out is that he was an active member of the Fieldston community both while in school and as an alum. As the pictures in the Fieldston yearbook in 1950 show, he was a member of both the soccer and swim teams. Toby Himmel, Fieldston’s former Alumni Relations Advisor, said that even though Jonathan lived in Asia and Europe for much of his adult life, he returned many times over the years to attend class reunions and ECFS events. His sister Reba Mirsky Goodman is a part of Fieldston’s class of 1945 and is an accomplished woman who ran a molecular biology lab at Columbia University. His father Alfred E. Mirsky, a pioneer in molecular biology, graduated from Fieldston in 1918, and their mother Reba Paeff Mirsky was an author of children’s books and a musician who taught classes at Fieldston Lower. Jonathan did not have any children; a few of his nieces are also alums of Fieldston.

You may be wondering, how did Jonathan Mirsky make it from the soccer field and pool at Fieldston to Tiananmen Square? After graduating from Fieldston in 1950, Mirsky received a bachelor’s degree in history from Columbia University in 1954 and a master’s degree in 1957 and then studied Mandarin at the University of Cambridge. In 1958 he moved to Taiwan, where he studied Chinese and Tang Dynasty history. In his words, “A trip like this was extremely unusual; no one could go to China in those days.” He received a Ph.D. in Chinese history from the University of Pennsylvania in 1966 specializing in the history of the Tang dynasty and became a professor of Chinese language and history at Dartmouth.

While at Dartmouth, Dr. Mirsky was an anti-Vietnam War activist and was even arrested for blocking a bus carrying draftees. When he visited China in 1972 with a group of Asian scholars dedicated to ending the war in Vietnam, he called himself a “Mao fan.” China at that time was in the throes of the Cultural Revolution, Mirsky spoke Mandarin and was able to see past the façade the Chinese government put on to look good to foreigners. “I returned to the hotel, stunned by what I had seen and heard,” Dr. Mirsky recalled in an account of the trip that was published in the 2012 book My First Trip to China: Scholars, Diplomats and Journalists Reflect on Their First Encounters With China. He came back to the U.S. and was one of the first scholars at that time to denounce the evils of the Mao regime.

In 1975, he moved to London and became a journalist. He continued to be a critic of China and its Communist rulers. He was also a critic of the Western leaders who he thought cared more about their strong economic relationships with China and were ignoring China’s human rights abuses.

In 1989 he was a reporter for the London Observer and witnessed the uprising and massacre of peaceful protesters in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. The Chinese police recognized Dr. Mirsky as a reporter and knocked out his teeth and broke his arm. But a fellow reporter helped to save him, and he still managed to dictate his story by phone. “Tiananmen Square became a place of horror,” Dr. Mirsky wrote in his article on the day of the crackdown, “where tanks and troops fought with students and workers, where armored personnel carriers burned and blood lay in pools on the stones.” Dr. Mirsky was honored with a British Press Award for his coverage of the Tiananmen Square massacre.

Dr. Mirsky was forced to leave China in 1991 for criticizing Chinese politics. After he left, he lived in Hong Kong and became East Asia editor for the Times of London but resigned in 1998 because he said the owner of the paper Rupert Murdoch told him to “go soft” on China. He was also a contributor to The New York Review of Books. Even in his late life, he never stopped writing to expose the evils of the Chinese government. “ I am reminded of the old street sweeper in 1990 at a corner in Beijing,” he wrote in 2014. “She was shoveling donkey dung into a pail. I asked her if she thought things had changed for the better. She replied, ‘This city is like donkey dung. Clean and smooth on the outside, but inside it’s still [dung].’ ”