During the explosive years of 1512-1570, the great European metropolis of Florence transformed from a Republic on the wane, to a flourishing duchy, then eventually the cradle of the Renaissance. It’s hard to imagine this period without the Medici, the successful merchant and banking family, at the helm, fruitfully advancing humanism in all cultural fields.

The Medici’s were able to dominate civic politics and shape culture through an ingenious combination of oligarchy and strategic patronage. The key figure in this transformation was Cosimo I de’ Medici (1519-1574), who became the second Duke of Florence in 1537 in the aftermath of his predecessor Alessandro de’ Medici’s assasination at the hands of his cousin Lorenzino de’ Medici. The astute Cosimo employed the arts as a political tool to promote himself and Florence, cementing Medici power for centuries.

As Fieldston Art Department chair Scott Wolfson said in an interview , “The Medici’s used art as a tool of propaganda. They ingeniously understood how art could be used to construct and enforce their perceived identity as powerful, important, worldly and wise individuals and family. By commissioning artists to create small and large scale public projects and private gifts, they further instilled the perception that they were deserving of their power. Through these artworks they ensured that their status would not only be in their lifetime but in perpetuity. Additionally, they understood how the social status of the artist was gaining traction. As artists such as Bronzino, Pontormo, Raphael and others gained popularity and fame, the Medici’s hired them for their commissions, which in turn, also elevated their own social status — there was a cache in hiring the most sought after artists. In short, the Medici’s created a powerful brand and meticulously controlled their image. The artworks they commissioned functioned as ‘really good advertising.’

The current exhibit at The Metropolitan Museum of Art offers a comprehensive view of Medicean Florence during the allotted period, centering the intersection between culture and Renaissance politics expertly. Over 90 pieces of painted portraits, books, manuscripts, armor, medals, busts and drawings all serve to demonstrate the effect of Cosimo’s transformative rule and patronage on the art of portraiture and what it would come to represent. The exhibit was curated by Keith Christiansen, the retiring chairman of the Met’s European painting department alongside Carlo Falciani, a professor of art history at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Florence.

The portraits selected introduce viewers to the various and nuanced ways in which artists portray the Florentine gentry under Medicean rules. Through portraiture, the artist has the ability to represent the sitters political and cultural ambition, significance and purpose, as well as their individual and collective identity expertly. Cosimo I’s patronage had an undisputed transformative effect on the art of portraiture itself and the rise of Late Renaissance Mannerism. This Late Renaissance style surfaced in the later years of the High Renaissance in Italy around 1520, replacing the emphasis on natural proportion, precision and poise with craft; elongated limbs, exaggerated perspective, contradictory proportions and complex poses.

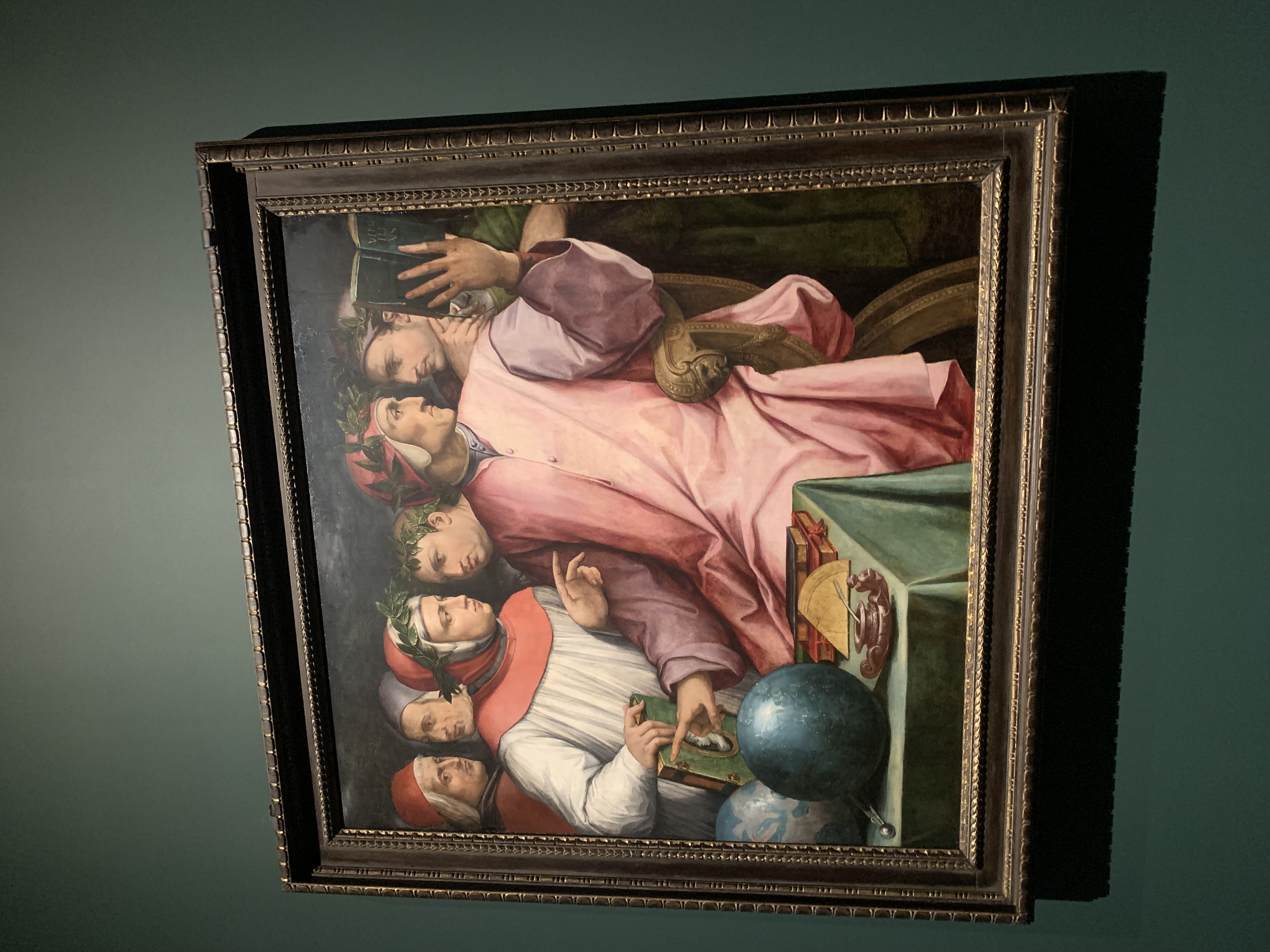

When Cosimo became Duke of Florence, the city’s political significance had been steadily fading. A select few knew better than Cosimo that the arts could be employed to advance personal and political agendas; so that is exactly what he did. Cosimo took advantage of the continual secularization of art and painting’s newfound interest in ordinary people. Cosimo also utilized painting’s increased status as a portable market product. Painting’s could now be copied and shipped throughout Italy and various countries in Europe, which presented the opportunity of promoting Cosimo, the House of Medici and Florence all together. The artists on view which accomplish this Medici-sponsored portraiture are dominated by Agnolo Bronzino, who became one of Cosimo I’s court painters in 1539 and is responsible for more than half of the painting on display. Following Bronzino, is his teacher Jacopo da Pontormo, Florentine school Rosso Fiorentino, Florentine goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini (who you may recognize from his bronze mannerism masterpiece of Perseus with the head of Medusa) and finally Cosimo’s court painter Francesco Salviati. Representing the old school High Renaissance style are a couple of stand alone paintings by Raphael and Andrea del Sarto.

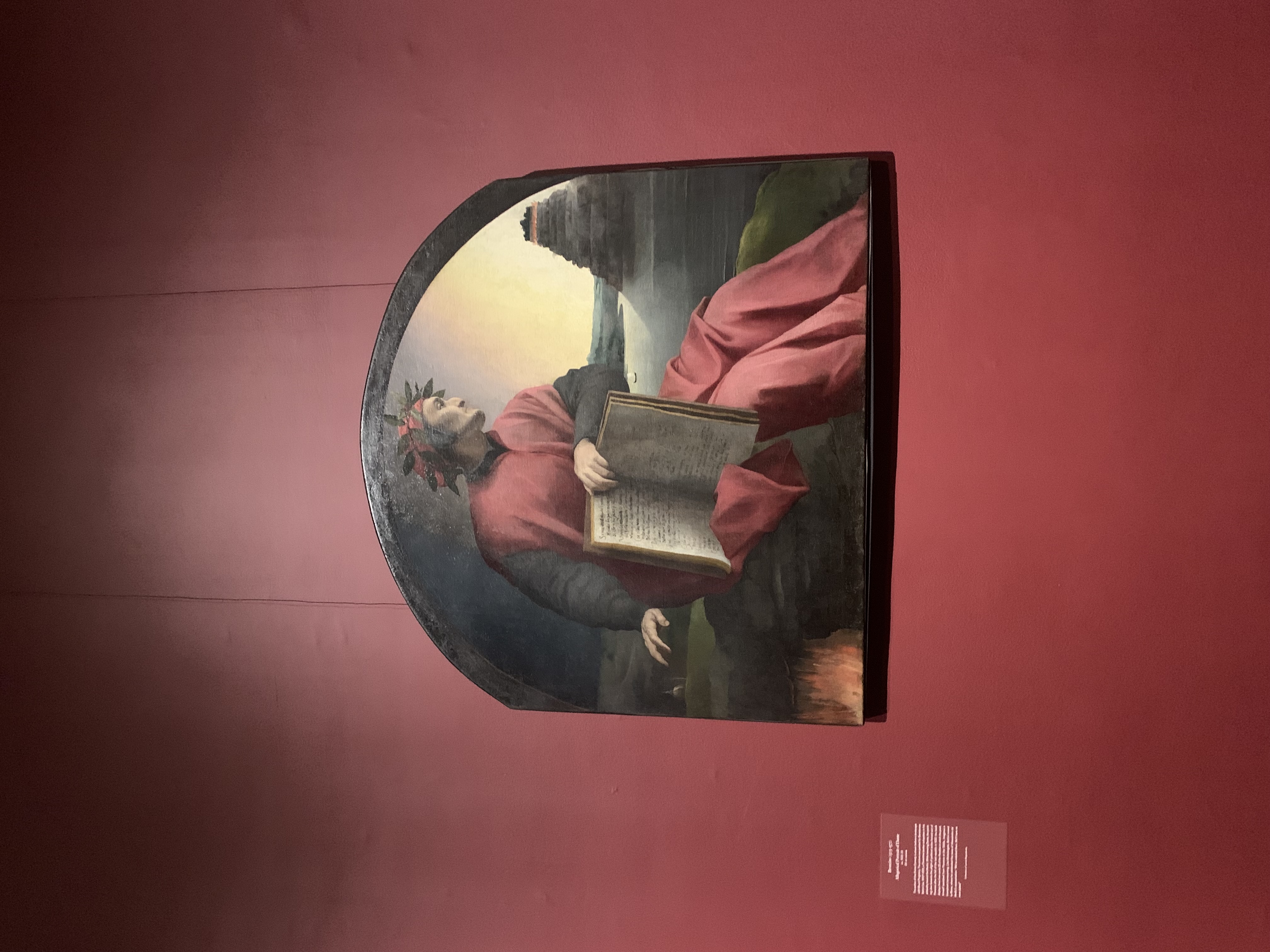

The exhibit walks us through the period through loosely themed vignettes, unpredictably shifting viewers focus from history to art history, literature, poetry and the revival of humanism, to family and succession. There’s nothing that can’t be cross-referenced or connected, fueled visually by consistent tension between differing artistic schools and styles of the artists on display. The first gallery after the introduction focuses on the years 1512 which saw the collapse of the Republic until 1532 when Alessandro de’ Medici became first duke of Florence. Florentine artists during this period reflected the traditional morals of the republic which were best represented by unembellished models of the Bible and the poetry of Dante. Portraits from this period championed purity and frankness rather than excessive decoration. Meaning was often conveyed through the inclusion of symbols or emblems which pointed towards the sitter’s social hierarchy or profession.

The second gallery introduces viewers to the deliciously chaotic back story of the Medici family’s relationship with Florence; exile, civil unrest, strategy, commerce, banking and patronage permeated their rule. This gallery also introduces viewers to the pivotal players in the formative years of Medici power; Lorenzo de’ Medici, Cardinal Giovanni, Cardinal Giulio eventually making their way to Alessandro de’ Medici. This gallery is followed by a thorough examination of Cosimo I de’ Medici’s lineage and dynasty. It follows how the 17 year old Cosimo asserted Medici power and continuity of the family’s dynasty, which is projected through the portraiture, often employed as diplomatic gifts to other high ranking European rulers to solidify his spot in the political sphere.

The subsequent two galleries look at Florentine Academia, one with a focus on the significance of literature, particularly poetry at the Accademia Fiorentina – a distinguished literary institution founded and funded by Duke Cosimo to further his artistic/cultural agenda – and the other focusing on how Duke Cosimo meticulously crafted the image of his duchy to be cradle of cultural rebirth. With fourteenth-century poets Dante and Petrarch at the center of attention, portraits depict words, authors and book titles to signify a sitter’s patriotism, social association, literary expertise, even political affiliation. As the byproduct of an intensely literary culture, artists embraced classical allegory and metaphor of their predecessors which can be seen through “disguised portraiture” in which sitter’s are depicted as a mythological figure. In the final gallery, the painters which dominated the exhibit and 1540s Florence, Francesco Salviati and Bronzino are shown in tension and comparison. The stylistic juxtaposition shows Bronzino’s portraits presenting a naturalistic, sensible style alongside Salviati’s illustrated and extravagant style.

Alongside and above the fleeting and frequently pursued objectives of wealth and territory by aristocrats of the past, Cosimo understood that which was most important and gained it through art; immortality.

On view at The Met 5th Avenue through October 11th