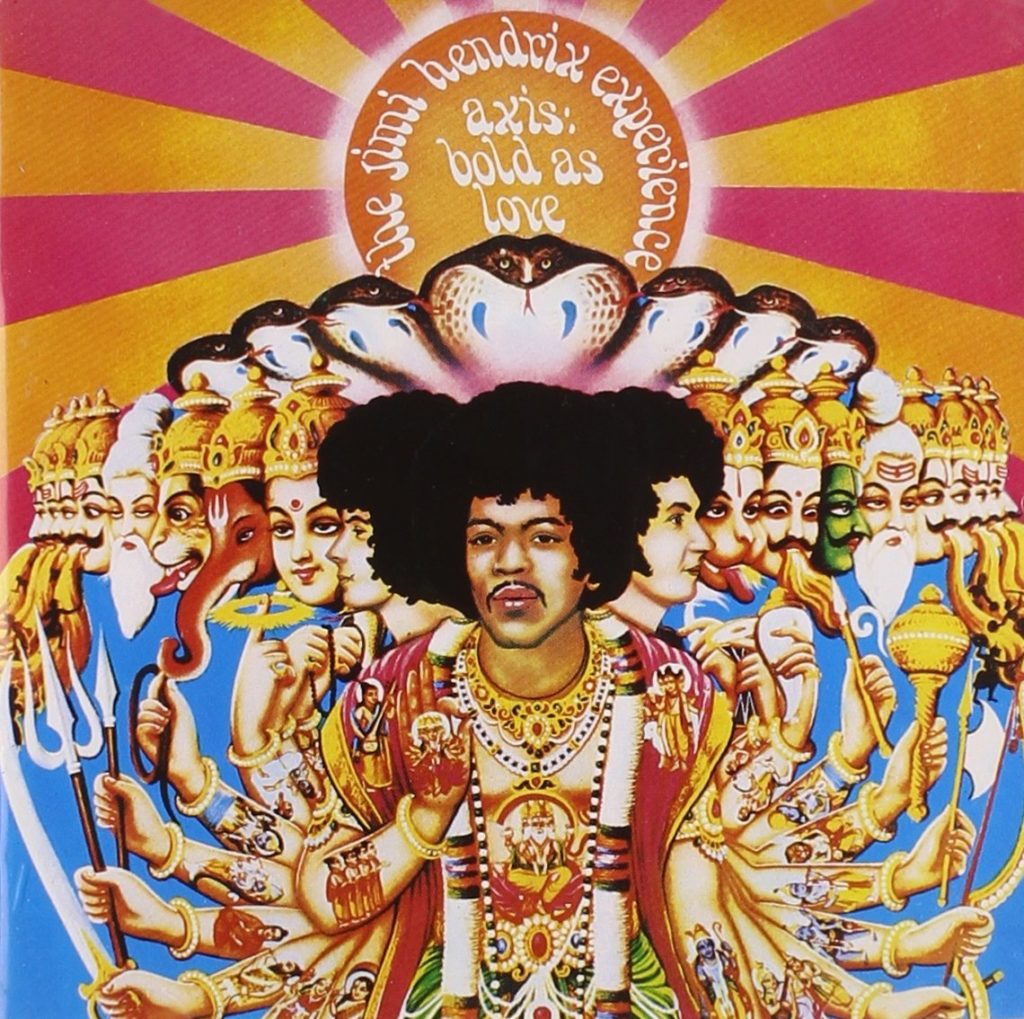

Nothing screams 1960s counterculture like the cover of Axis: Bold as Love. It was appropriated from Viraat Purushan-Vishnuoopam, an image so famous in India that its ubiquity can only be compared to that of images of Jesus Christ in the Western World. This time, instead of Vishnu, the Hindu god, it is Jimi Hendrix, the hippy god. There’s a reason why it was banned in Malaysia–it is bold, blasphemous, and trippy. Whether Hendrix intended it or not, it reads as a colossal middle finger to mainstream America, replacing Christianity with Hinduism, and the white and holy Jesus face with a Black, Cherokee psychedelic rockstar–all just a few years after the end of Jim Crow. Instead of a traditional religion, it represents the cult of flower power: the creed of peace, love, and a lot of LSD. And the whole thing was an acid-dipped mistake.

Though it can be perceived as a statement about the hippie lifestyle and is analogous to its relationship with Eastern faith, the flamboyant cover of Axis: Bold as Love was really just a giant mistake. Hendrix said that “the music in Axis is based on a very, very simple American Indian style,” and he wanted to pay tribute to his Cherokee roots on the album cover. However, his record label confused his reference to India with the South Asian country, and Roger Law placed the image of Hendrix and his bandmates on that of an Indian religious poster. Hendrix claimed: “‘The three of us have nothing to do with what’s on the Axis cover.’” The image used on the cover, a Hindu devotional painting called Viraat Purushan-Vishnuoopam, depicts the Supreme God Vishnu, with Krishna in the center representing mankind, the evil deities to the left, and the good deities to the right, representing the balance between good and evil.

The cover art, albeit a mistake, accurately represents the hippie ethos. In fact, its accidental nature is akin to that of the counterculture’s obsession with Eastern religion; though a genuine spiritual endeavor for some, for many hippies and rockstars, Indian iconography was little more than a psychedelic fad, a natural byproduct of the hippie lifestyle. The counterculture movement, as it descended from movements such as the Beats and Transcendentalism, both of which were greatly influenced by Eastern faith, shares many core tenets with Indian religion. Beyond just the practice of meditation and yoga, the idea of spiritual liberation is central to both cultures. The ultimate objective of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism–deliverance from the endless cycle of rebirth–is only attainable by overcoming all earthly desires. The hippie emphasis on nonconformity, on “dropping out” or liberating oneself from the evils of mainstream culture, and the inner peace that follows, sounds a lot like the Indian beliefs of moksha and nirvana. The Indian emphasis on asceticism is echoed by the counterculture’s renouncement of all things mainstream; to embrace the hippie lifestyle was to abandon one’s ties to the most conventional of American values.

Most “hippies” were white, middle class young adults, who, because of economic prosperity, had all the time in the world to protest and do drugs. Representative of a societal, generational tension, they rebelled against the values of their parents: segregation, the Vietnam War, an obsession with materialism, traditional gender roles, homophobia, and the Western way of life. Instead, they sought a lifestyle of peace, love, sex, and drugs. Thanks to the emergence of birth control pills, the availability of Mexican marijuana, and a huge number of baby boom youth, the flower power movement took America’s youth by storm. At that time, psychedelic drugs such as LSD were legal, and were the perfect outlet to transcend consciousness and explore spirituality. From their purple haze came a fascination with meditation, yoga, astrology, Native American mysticism, and Eastern religion.

Half a rejection of their parents’ values, and half the perfect supplement to an acid trip, hippies were fascinated with Eastern religion, primarily Buddhism and Hinduism. The 1960s counterculture is often considered as the heir of the Beats. The term “Beat Generation” was coined in 1948 to describe an underground youth movement, and was a rebellion against all things traditional, conservative, and conventionally American. They passed down their interest in Eastern religion, particularly Zen Buddhism, to the hippies. A 1970 article in Time Magazine describes Zen Buddhism’s core tenets of “inward meditation versus doctrine, of emphasis on the visceral and spontaneous as against the cerebral and structured, of inspiration rather than linear ‘logic’”–all the things that would fascinate a hippy on shrooms.

Hippies were also drawn to Hinduism, inspired by Indian teachers and gurus who taught in America as early as the 1890s. Some of them, including Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, who the Beatles lived with in India in 1968, became celebrities, and encouraged Americans to experiment with yoga, meditation, and mysticism. Although Indian gurus advised them against it, hippies used marijuana and hallucinogens as a gateway to spiritual enlightenment. Thus, the hippie obsession with Eastern mysticism was more a fetisization than a genuine religious movement. Soon, hippies from all over burned incense, had Buddhas in their houses, listened to Indian music, wore mala beads and colorful Indian-style clothing, became vegetarian, and meditated. Like the Hendrix album cover, Eastern mysticism in counterculture was simply the product of a lifestyle of peace, pot, and peyote.

Another staple of the counterculture movement was psychedelic rock. There was literally an entire music genre in the late 1960s that was devoted to drugs–the strange psychedelic noises in the middle of songs, the use of electronics, the deafening sound of feedback, and the loud, roaring electric guitar. Its birthplace was the Golden State, where the early Grateful Dead performed at Ken Kesey’s Acid Test multimedia “happenings.” The movement spread like a wildfire from San Francisco across the country and over to Europe, absorbing some of rock’s greatest bands: Jefferson Airplane, Quiksilver Messenger Service, and Big Brother and the Holding Company in San Francisco; the Doors and the Byrds in Los Angeles; the Velvet Underground in New York City; the Yardbirds (and later Led Zeppelin), Jeff Beck, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, the Rolling Stones, Donovan, the Kinks, early Pink Floyd, the Who, and the Beatles in England. This music was not only inspired by psychedelics–some of the most famous songs of the era, such as the Beatles’ “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” and “With a Little Help from my Friends” were a love letter to them.

San Francisco was the Mecca of the counterculture movement. Not only was it the birthplace of psychedelic rock, but it famously attracted about 100,000 people to its Haight-Ashbury neighborhood for the Summer of Love in 1967. There, music, hallucinogenics, free sex, and political activism flourished, as the hippie lifestyle, for the first time, was brought into the global spotlight. However, “‘the ultimate high’” and ‘“the major spiritual event of the San Francisco hippie era’” took place not during the Summer of Love, but months earlier at a fundraiser for a Hindu organization.

Mantra-Rock Dance started as a local benefit to raise money for the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), or Hare Krishna, and its first center on the West Coast, smack in the middle of Haight-Ashbury hippieland. ISKCON was founded by A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, a guru in the school of Vaishnavite Hinduism, which worships Krishna as its central deity. Within a few years, his group was a spectacle on the streets of New York with their signature yellow robes, shaved heads, street dancing and chanting, classes, and free food for the community. In 1966, he chose Mukunda Das to spearhead the establishment of a San Francisco temple in late 1966. So, in an effort to fundraise and gain followers, he decided to indulge in San Francisco psychedelia and host a rock benefit at the temple. Of course, this decision invited a lot of controversy among the group. They preached abstention from alcohol and drugs, celibacy and monogamous marriage, but they knew everyone there would be drunk, high, sexually active and polygamous. However, the Beat poet Allen Ginsberg convinced Prabhupada that “there was a spiritual hunger that he could fill.” Prabhupada agreed.

Within days, psychedelic posters for the event lined the streets of Haight-Ashbury and the nearby colleges. The flier, designed by Harvey Cohen, one of the first Hare Krishnas, is second only to Axis: Bold as Love with its psychedelic imagery: Prabhupada sits at the bullseye of a purple spiral floating above a pink spiral. In crooked purple letters reads: “Bring cushions, drums, bells, cymbals, proceeds to opening of San Francisco Krishna Temple.” Performing at the benefit were the Grateful Dead and Big Brother & the Holding Company with lead singer Janis Joplin, two of the Bay Area’s most popular psychedelic bands, and Moby Grape, a then little known band whose performance that night would earn them acclaim and a record deal. When Prabhupada arrived on the West Coast, the San Francisco Chronicle asked him if he would let in the hippies, and he said, “‘Hippies or anyone––I make no distinctions. Everyone is welcome.’” By 8 PM on Sunday, January 29, hippie heaven was open for business.

3,000 hippies flocked through the doors of the Avalon Ballroom for $2.50 per person and into psychedelic Narnia. Also in attendance was a lot of marijuana and a lot of LSD, courtesy of Harvard acid enthusiast Timothy Leary and his buddy Owsley Stanley III, the manufacturer of notoriously potent LSD, who were handing out hundreds of hits in the crowd. Satsavarupa Dasa Goswami, Prabhupada’s biographer, sets the scene:

“Almost everyone who came wore bright or unusual costumes: tribal robes, Mexican ponchos, Indian kurtas, ‘God’s-eyes,’ feathers, and beads. Some hippies brought their own flutes, lutes, gourds, drums, rattles, horns, and guitars. The Hell’s Angels, dirty-haired, wearing jeans, boots, and denim jackets and accompanied by their women, made their entrance, carrying chains, smoking cigarettes, and displaying their regalia of German helmets, emblazoned emblems, and so on—everything but their motorcycles, which they had parked outside.”

At about 10 PM, following a trippy Hindu light show and a meal of sanctified orange slices, Prabhupada made his entrance. His biographer described: “He looked like a Vedic sage, exalted and otherworldly. As he advanced towards the stage, the crowd parted and made way for him, like the surfer riding a wave. He glided onto the stage, sat down and began playing the kartals [ritual finger cymbals].” Allen Ginsberg introduced and welcomed Prabhupada to the stage, but somewhere along the way spoke of chanting as the perfect descent from their high and a way to “‘stabilize their consciousness upon reentry.’” After Prabhupada addressed the audience, Ginsberg led them in the Hare Krishna chant, which, after a few minutes, broke out into a full on flash mob. Prabhupada was the first to begin dancing. He was soon followed by the members of the bands, who accompanied it with their instruments. The crowd played along with their instruments and danced into the night. Afterwards, the Grateful Dead and Big Brother & the Holding Company played hours past midnight.

The event was a smashing success. Not only did it raise $2,000, but membership skyrocketed at the temple and Prabhupada rose to national prominence, going on speaking tours across the country and establishing dozens of temples. Soon, members of the ISKCON San Francisco Team were sent to London, where they famously befriended George Harrison and the Beatles.

In February 1967, Harrison’s wife, Pattie Boyd, saw a newspaper ad for Transcendental Meditation classes. Boyd, who was seeking spirituality in her life, began attending the classes, and her husband soon joined her. In August, the Harrisons and the rest of the Fab Four sat in on a lecture in London by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the leader of the Transcendental Meditation movement. Boyd wrote in her memoir, Wonderful Tonight, “Maharishi was every bit as impressive as I thought he would be, and we were spellbound.” That same group, alongside Mick Jagger and Marianne Faithful, then attended a ten day conference of the Spiritual Regeneration Movement in Bangor, Wales. It was there that the Fab Four announced that they would finally say goodbye to drugs. “‘It was an experience we went through. Now it’s over and we don’t need it any more,’” said McArtney. However, while they were at the conference, they received news of the tragic death of their manager, Brian Epstein. As a result, Maharishi invited the Fab Four to live at his ashram in Rishikesh.

The Beatles, their wives and girlfriends, along with singer Donovan, actress Mia Farrow, Mike Love of the Beach Boys, arrived in India around February, 1968. The ashram was a lot like one of those “socialist summer camps” Alvy Singer rambles about. It was built in 1963 on a fourteen acre plot in the forest. There were six long bungalows, each with five or six double rooms, and flowers and greenery all around. George Harrison and John Lennon were there to meditate. They were fascinated by Maharishi’s words, and were finally able to sit back and relax after years of drugs and fame. Paul locked himself in a room for five days to meditate and wrote hundreds of songs. George did not fool around when it came to his spiritual journey. Paul McArtney recalls, “‘He was quite strict. I remember talking about the next album and he would say, ‘We’re not here to talk about music–we’re here to meditate.””After a long day of lounging, meditation, and songwriting, all the musicians would play together. Their photographer, Saltzman, wrote “‘The weeks the Beatles spent at the ashram were a uniquely calm and creative oasis for them: meditation, vegetarian food and the gentle beauty of the foothills of the Himnalayas. There were no fans, no press, no rushing around with busy schedules, and in this freedom, in this single capsule of time, they created more great music than in any similar period in their illustrious careers.’”

That great music he was referring to, of course, was the White Album. Sophomore Sarah Abenante, a Beatles fanatic, is struck by the diversity of their 1968 masterpiece. record. Their longest record, it shows just how versatile the group is. Recent graduate Lucas Cohen describes it as groundbreaking. Their first album after their psychedelic period, the Beatles’ 1968 masterpiece was the brainchild of all the artists on the retreat, not just the Fab Four. Donovan was not only a friend to the Beatles, but he was a mentor. Harrison was in awe of Donovan’s descending chord patterns, which he then used to write “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.” Donovan taught John Lennon his fingerpicking style on the guitar. In his 2005 autobiography, Donovan wrote “‘My new pupil went to it with a will and he learned the arcane knowledge in two days.’” He employed this new style on “Julia” and “Dear Prudence.” The latter was about Mia Farrow’s little sister, Prudence Farrow. George and John were worried about her, and wanted her “to come out and play” as she spent hours in her room meditating with the door locked. Mike Love, when he heard McCartney playing the acoustic guitar to what would be “Back in the USSR,” said to him, “‘You know what you ought to do. In the bridge part, talk about the girls around Russia. The Moscow chicks, the Ukraine girls, and all that’… If it worked for ‘Califronia Girls,’ why not for the USSR?’” The people that inspired “The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill” were an American college graduate and his mother, who, on elephant back, shot and killed a tiger on a hunt. It wasn’t just the White Album. Donovan’s “Hurdy Gurdy Man,” a staple of the psychedelic era, was written in India. Some of the songs written there landed on Abbey Road and in the Fab Four’s various solo careers; Lennon’s “Jealous Guy”, McCartney’s “Junk” and “Teddy Boy,” and George Harrison’s “Circles and Sour Milk Sea.”

George Harrison practiced Hinduism, specifically Hare Krishna, until the day he died. In 1966, he traveled to India to study the sitar, and it was there that he met Maharishi for the first time. Beyond just an escape from the drugs and the stardom, he needed to see God to believe it. In the introduction to Swami Prabhupada’s book Krsna, “If there’s a God, I want to see Him. It’s pointless to believe in something without proof, and Krishna consciousness and meditation are methods where you can actually obtain God perception. In that way, you can see, hear and play with God. Perhaps this may sound weird, but God is really there next to you.” When he died on November 29, 2001, at age 58, he was surrounded by images of Lord Rama and Lord Krishna. In his will, he left 20 million British pounds for ISKCON, and wished for his body to be cremated in the Ganges in India, a holy site in Hindus. His faith was very evident in his music, as seen in the albums The Hare Krishna Mantra, My Sweet Lord, All Things Must Pass, Living in the Material World and Chants of India. His most popular song, My Sweet Lord, equates “Hare Krishna” with “Hallelujah.” In 1969, the Beatles produced the single “Hare Krishna Mantra,” which Harrison performed alongside the congregants of the Radha-Krishna Temple. He has songs with references to the Bhagavad Gita, to Prabhupada, to yoga, and the list just goes on.

Evidently, the Beatles’ interest in Indian religion was not merely a fad. Unlike Jimi Hendrix, the Grateful Dead, and Big Brother and the Holding Company, the Beatles did not think of Hinduism as just an acid trip. They did not appropriate Indian iconography for a psychedelic aesthetic, or to make a statement about the hippie lifestyle. Nothing about their interest in Hinduism was tokenistic. It was 100% spiritual and creative. All of this music, regardless of whether or not it explicitly mentioned religion, was created with Hinduism as the backdrop. It is no coincidence that they were perhaps at their creative apex at that ashram; they meditated, reflected, and liberated themselves from the troubles of their lives. Thus, the Beatles’ relationship with Hinduism is representative of the portion of the hippie population that did genuinely adhere to Eastern faith: the population who didn’t just wear Indian clothing and pick and choose a few traditions to fit a trend.

It is no surprise that many hippies were attracted to Indian religious traditions–with a tablet of LSD, these connections were not only potent, but likely felt otherworldly. However, therein lies the contradiction between genuine devotion to Eastern tradition and psychedelic rock. The obsession with Eastern imagery in the rock and roll world was little more than a fad and a giant trip. Not only did it fit the hippie mantra, but it was the ultimate psychedelic aesthetic. The Rolling Stones used an image of a Buddha on the poster for their infamous Altamont Speedway Concert, which had no relation to Buddhism whatsoever. All Roger Law needed to do was put Jimi Hendrix’s face on Krishna’s and replace the blue background with pink and gold to make it a staple of the psychedelic era. Likewise, Mantra-Rock Dance, though part of a genuine religious movement, was hosted with the expectation that people would go there to get high and maybe donate along the way. For rockstars, the use of Indian iconography was of religious significance, not to Buddhism or Hinduism, but to hippie-ism and everything that it represented: peace, love, nonconformity, and, above all, drugs.

superior, sensitive; surprisingly well- written by a high school student;

Hendrix claimed: “‘The three of us have nothing to do with what’s on the Axis cover.’”

Then why does album cover and the title song “Axis Bold as Love” absolutely reflect the Kurukshetra battlefield where Arjuna’s hears Krishna sing the Bhagavad-gita to convince him to do his duty and fulfill Krishna’s orders? (“Once happy turquoise armies lay opposite ready But wonder why the fight is on”) Yes, that’s Arjuna’s angst at the thought of slaying his relatives (“My yellow in this case is not so mellow In fact i’m trying to say it’s frightened like me And all these emotions of mine keep holding me from, eh Giving my life to a rainbow like you”). But Arjuna, being convinced by the Lord Himself eventually is fully convinced. This reflected by the soaring guitar solo at the end as the battle commences. Hardly a coinky-dink, methinks.

P.S. Just ask the axis (He knows everything)

great essay