Following the death of George Floyd, race has been at the forefront of Americans minds. With the resurgence of The Black Lives Matter movement came a national reflection and moral judgement centered on the topic of race. Since the 1960’s, there hasn’t been a time where we have examined race in America on such a paramount scale. As the school year nears, our teachers have decided to embrace these realities in our curriculum. Because of this, Vinni Drybala, outgoing Chair of the English Department, created a kind of “Baldwin Initiative” for the Upper School English department, which will read Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time in all English classes in all upper school forms.

“Reading Baldwin” Drybala said, “gives us an opportunity to not only understand the current moment, but also to see how the literature we read in our courses provides context to the moment. By this I mean that our courses have always implicitly studied the way power structures are created and upheld, how oppression and privilege are intertwined, and how story and narrative create pathways for resistance. These ideas are what has always grounded Fieldston literary study in social justice. But framing these ideas through Baldwin’s work gives it an explicit frame at an important historical juncture — for our school and beyond.”

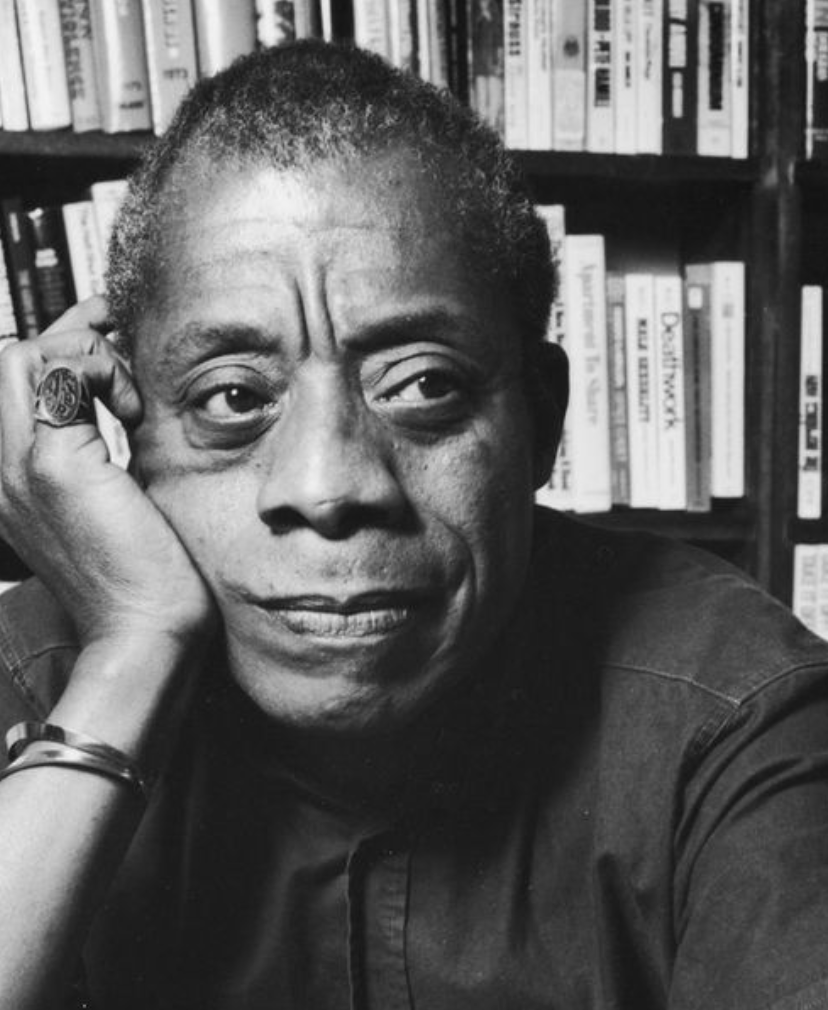

While James Baldwin has been an important American voice since the late 1940s, he is having a tremendous resurgence of popularity. Because his words and stories eerily echo the sentiments that so many of us feel today, it’s hard to believe he hasn’t been writing every day since his death in 1987.

Baldwin was born on August 2nd 1924 in Harlem and was disenfranchised from the start. He was the eldest of nine children and grew up impoverished with his mother Emma Berdis Jones. She worked as a cleaning woman to support herself and James; he never knew his biological father. In 1927, his mother married a Baptist preacher named David Baldwin with whom she had eight children. His stepfather was an inexorable man with a terrible temper who Baldwin would escape from with his insatiable appetite for literature from a young age. In the “Autobiographical Notes” to his first collection of essays, Notes of a Native Son, he writes “I read Uncle Tom’s Cabin and A Tale of Two Cities over and over and over…In fact, I read just about everything I could get my hands on — except the Bible, probably because it was the only book I was encouraged to read.”

At the age of fourteen he underwent a Christian religious awakening and began a successful, yet short lived, preaching career following his stepfather. He wrote about this period of his life in his semi autobiographical first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain and in his play about an evangelical woman, The Amen Corner. After David Baldwin died in 1943, days before Baldwin’s nineteenth birthday, Baldwin buried his stepfather and moved to Greenwich Village at the beginning of “The Beat” Era. He embarked on a series of ill-paid jobs, literary apprenticeship and self enrichment all part of the true bohemian spirit he hoped to embrace. These were the formative years where Baldwin developed his writing style and established himself as a journalist, an essayist, and a novelist. He started out with reviews and essays written for The Nation, Partisan Review, Commentary, Dissent, The New Yorker, Time and other magazines. Here he laid the groundwork for the themes he would explore and develop in his later works.

In 1948, Baldwin decided to leave the country and move to Paris. In an interview with television talk show host Dick Cavett, and Paul Weiss, Baldwin famously remarked “When I left this country, in 1948, I left this country for one reason. I didn’t care where I went; I might have gone to Hong Kong, I might have gone to Timbuktu, I ended up in Paris on the streets of Paris. With 40 dollars in my pocket and the theory that nothing worse could happen to me there that had already happened to me here (America).”

Postwar Paris had become a refuge for a number of expatriate Black Americans at the time (Richard Wright, Dexter Gordon, Bud Powell, Miles Davis). Although it was not without its racial prejudices, “In Paris” Baldwin said, “I didn’t feel socially attacked but relaxed, and that allowed me to be loved.” Shortly after Baldwin’s arrival in Paris, he met a seventeen year old Swiss artist named Lucien Happersberger. The fact that Baldwin was Black and Happersberger was white was less of a transgression than it would have been back in the States. Lucien was one of the men on his sexual journey that led him to be attracted to straight and bisexual men. The reality that Baldwin found himself primarily attracted to men who wouldn’t reciprocate, increased a sense of isolation he fed on and projected in his work. Lucien was his great love and even he was primarily attracted to women.

In 1956 Baldwin published his second novel Giovanni’s Room which traces a tragic affair between two men – a white American drifter and an Italian bartender amid the bars of postwar Paris. Giovanni’s Room remains his seminal novelistic exploration of queerness in his world; as well as a stunning evocation of shame shaped by his trials and tribulations of love in Paris.

In 1957 he returned to the United States and became an active participant in the civil rights movement that had swept the nation. He befriended major political figures such as Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr. and Medgar Evers. He joined the Congress of Racial Equality which allowed him to travel across the South lecturing on his views of racial inequality and became a powerful voice in the movement. His insights into both the North and South gave him an incredibly unique perspective on the racial problems the United States was facing. His essays on the movement were published in major magazines such as Harper’s, The New Yorker, and Mademoiselle.

As a writer and public intellectual, James Baldwin liberated the thinking of Black Americans and homosexuals by affirming the humanity of each group with the words that he spoke and wrote. He confronted white America and the time-honored Western World and said “I am not your negro.” That phrase, “I am not your Negro,” recently became the title of a documentary by Raul Peck, about Baldwin, and Baldwin’s famous debate over race and the American Dream with the conservative thinker and celebrity William F. Buckley, Jr. at Cambridge University.

When doing research for this article I came across an interview with Baldwin where he was asked by a journalist “When you were starting out as a writer, you were Black, impoverished and homosexual. You must have said to yourself, Gee, how disadvantaged can I get?” Baldwin then said “No, I thought I had hit the jackpot. It was so outrageous, you had to find a way to use it.” and he did just that.

He was not a one dimensional man but a man who could see the world through different lenses and aspects of his identity. He denounced the presumed fraternity of Black writers, academics, and intellectuals as he wrote in 1959 during his self imposed exile in Paris that he had left America because he wanted to prevent himself from becoming merely “a Negro writer.” Although he has become one of the greatest Negro writers of all time, he is also so much more. He has become a writer who captures the grimmest parts of humanity and struggles for a diverse range of readers. He was an articulate witness to the consequences of American racial strife. His success in transposing the discussion of American race relations and sexuality resonates with readers to this day and has forever expanded the American imagination.

Baldwin’s ability to capture the Black experience and insistence on being inside his subject explains why his writing remains brilliantly alive in the 21st century. In the time of Black Lives Matter and the outrage people of color feel for violence against the African-American community, systemic racism, anti-blackness and so much more; it often mirrors the same struggle and outrage Baldwin was surrounded by in his day. We’ve renewed attention to the high-profile deaths of Black Americans during the past decade and ongoing conversation about systemic racism operating through our country’s most powerful institutions. Because of this, it’s vital to revisit Baldwin’s voice and the instruments he’s already given us to navigate such conversations.

When discussing Baldwin and his relevance today, Upper School English teacher Michael Morse shared some insight into the English department ‘s decision to include Baldwin in the curriculum:

“So our work this summer includes a department-wide reading of James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, as the aim is for each of us to start the year with Baldwin’s text. We want to use Baldwin‘s work as a lens through which we can consider the skills and content we cover in our classes. It’s important—as members of a predominantly white department who work with students in all four years of Upper School— to examine our positionality as we reimagine our own centers and curricula as we consciously strive to decenter whiteness and better support our students. Personally, I’m thinking a lot about three cornerstone moments in our nation’s history and responses to those moments: Civil War and Reconstruction, the civil rights movement in the mid-20th-century, and our recent Obama presidency and the Start of the BLM movement. Each of these historical moments has been countered by White Supremacy and calls to protect a kind of illusory “American innocence.” Whether we’re looking locally at our own imperatives from SOCM or this past summer’s legislation to remove qualified immunity in New York State, or thinking nationally and globally as with this summer’s resurgence of BLM, we can continue to learn from Baldwin‘s moments of anger and sorrow and optimism. What might it mean for us as an institution to use Baldwin as a lens to look at what we assign and read in our curricula? We’re facing two pandemics and all-important moments of moral reckoning; Baldwin can help us see how we’ve faced similar moments of moral reckoning and better gauge how we might respond with more empathy and success than we have in the past.”

Now is the time to learn from Baldwin’s optimism, realism and strong convictions. He believed it was his duty to remain in touch with young African-Americans and give a voice to the voiceless. Although he may not have always agreed with everyone in the civil rights movement, he understood the roots of their rage and was able to be respectfully critical. Unlike peers such as Malcolm X, who offered a particular solution to the crisis at hand, Baldwin’s job was to bear witness and chronicle the events that were unfolding. He helped us see the injustices that were taking place more personally and clearly, then left it up to us to draw the conclusions. Let us continue to embrace his words and the valued timely lessons they convey, to help us continue to draw our own conclusions today.

Beautifully written, richly researched, and a thoughtful, nuanced take on the writer and his place in the curriculum and the world at large. Thank you.